So You Want to Write a Song?

Tips on Songwriting by Adelaide de Beaumont (Lisa Theriot)

Asking, “How do you write a song?” is much like asking, “How do you build a house?” [1] That’s a big question, one which contains a whole bunch of little questions (“How do you pour a foundation?” “How do you install plumbing?”). There are people who produce piles of lyrics but claim they “can’t write music,” people who make up tunes all day but don’t know where to start with words, and people who don’t know where to begin either process. My process looks something like this:

- I get AN IDEA.

- I write some words.

- I start to write a melody. <%&$^*>

- I fix some words.

- I tinker with the melody. <&^$%^>

- I get sick of it and throw it into a corner.

- I dust it off and decide I like it enough to finish it.

- It’s a song!

On some rare occasions, my Muse blows pixie dust into my ear and I go right from step one to step eight. Sometimes, pieces get stuck at step six and never see the light of day. But usually, it’s a process of vision and revision. I am a wordsmith; for me, the words come first 99.9% of the time. If you are a melody-first person, some of your steps will change order, but you’ll find the process isn’t all that different.

Adelaide‘s Punchbowl Theory of Songwriting™

Someone who lives alone in a cave, doesn’t hear music, and doesn’t read stories CAN’T WRITE SONGS. You can only get out what you put in. I think of it as an enormous mental punchbowl; every tune you hear and everything you read or experience goes into the punchbowl, and it churns around. Then, when you’re writing, you try to dipper into the punchbowl and see what comes out (easier said than done, I know). The punchbowl tends to have layers, though, so if you’re listening exclusively to one genre, one artist, etc., that’s going to be the top layer, and when you dip in, you’re going to get only that unless you do some stirring.

We can’t help ourselves. In inventory accounting, it’s called LIFO, or “last-in-first-out.” We tend to be influenced more by the last opinion we hear before making a decision. We are pattern thinkers. If you’ve ever heard the expression, “When you hear the thunder of hooves, you think horses, not zebras,” that’s the same idea. Our brains want to follow the paths they are already on. If you’ve been reading Jane Austen novels for weeks, and you sit down to write a letter, you’ll find it has some turns of phrase from Jane Austen, whether you intended it or not. If you listen to Stan Rogers for weeks and sit down to write a song, don’t be surprised if it sounds like Stan Rogers. This can be a good thing; there are far worse things than writing a song that sounds like Stan Rogers. If you want to write a song that sounds like Stan Rogers, then listening to nothing but Stan Rogers for awhile is a good first step. (Even if you end up with no song, you’ll have heard some good music.)

But wait, I hear you say, all Stan Rogers’ songs don’t sound the same! Remember the “we are pattern thinkers” bit? You’d be surprised if you really analyze someone’s complete body of work how many patterns you find. And happily, because our unconscious minds are looking for these patterns, we can pick them up whether or not we have any training as an editor or musicologist. Haven’t you ever heard something and thought, “that sounds like the Beatles <insert a favorite defunct group here>,” when you knew it wasn’t? You may have been picking up on musical intervals, language, style of instrumental accompaniment; you can’t put your finger on it, but something made you think X when you heard Y. You were conditioned to expect horses by the sound of hooves (the zebras were a surprise).

If your goal is to produce a work in a particular style, then immersing yourself in that style is a good idea. If you want to write a piece in the style of the Cantigas de Santa Maria, listen to only the Cantigas for as long as you can stand it. Your brain will learn the range, timing, and intervals of those songs and spin them around in your head. It will actually be hard NOT to get out a melody that sounds like part of the Cantigas. (You’ll then have to find someone to listen to your piece and tell you whether it’s EXACTLY like one of the Cantigas. See “Is it Original?” below.)

On the other hand, that might not be the most creatively satisfying option. The beauty of art is that we are individuals; MY punchbowl does not have the same ingredients as YOURS. The more we stir, and the more we create based on our unique punch recipes, the more the songs will sound like us. If your goal is to write SCA-inspired popular pieces, you’ll probably find you get better results using your whole punchbowl, because it’s probably not too different from the punchbowl of your target audience.

So how do you stir? Another funny thing about brains—our memories are tied like knots in a fishnet. If you bring up one knot, you also bring up all the knots near it. Listen to a favorite album you haven’t heard in awhile, watch an old movie, flip through a yearbook. Then sleep on it. The next day you’ll find things popping up in your head that wouldn’t have been there otherwise. (Please do not blame me for any psychotic episodes from old repressed memories. I am not responsible for the potentially toxic contents of your punchbowl. Mine is toxic enough.)

If you feel that you’ve stirred and still aren’t happy with what’s coming out, maybe you need to add some ingredients. Listen to musical theatre, old standards, music hall, and traditional tunes, especially if you don’t usually, and you’ll have different ideas about where to go after the first note. (Avoid jazz, unless you’re trying to write jazz, or unless you want the thunder of hooves to actually be zebras.) Remember, the more that goes into your punchbowl, the more options will sound good to your brain when you set out to work on your piece.

The punchbowl applies to initial ideas, music, and lyrics. If your lyrics sound like they were written by a fourth grader (and not a particularly bright fourth grader), you’re probably not putting enough good words into the punch bowl. Even if you read the Cliff Notes in High School, READ Shakespeare. Even for SCA pop, read Tennyson, Kipling, Howard Pyle and other romantic Victorian lads who yearned for days of yore just like we do. Not only will you pick up words you didn’t know before (don’t skip over them, look them up!), but you’ll take in a fluidity and elegance to language that is pretty rare in modern writing. Read poetry. See how people get big ideas into few words. Read the Bible, Aesop’s Fables, and other collections of stories with which a medieval audience would have been familiar. Chaucer. Marie de France. Boccaccio. The more you put in, the more there is to pull out and put on the page.

Where do ideas come from? (Or, Only Steal From the Best)

I jest, obviously. But there is nothing new under the sun. Chaucer wrote about Hercules in The Monk’s Tale, which he got almost entirely from Boccaccio’s work, “De Casibus Virorum Illustrium.” (“Examples of Illustrious Men”) Boccaccio got it from reading Ovid. Just because “it’s been done” doesn’t mean it can’t be done again. There are a variety of pre-1600 sources for stories about King Arthur, Robin Hood, Hercules, and many other guys (and a few girls) we’re still making movies about today. To the list above in the “punchbowl” section I could add Bede (The Anglo-Saxon Chronicles), the Mabinogian, Homer, various chansons de geste, etc. TONS of material. Whatever your culture, I bet they had a favorite story collection (or several).

A lot of us write songs about SCA reality. And let’s face it, nothing will get a crowd behind you like doing a song that boils down to, “Our kingdom rocks!” But remember that with the exception of a dinosaur minority <cough>, the SCA “generation” is 3-5 years. Writing a song about when Sir So-and-so got his whatsit caught in the shield wall may not be funny a little ways into the future when Sir So-and-so no longer plays and no one knows who you are talking about. Be sure it’s really funny and doesn’t depend on knowing the person in question, or you may find yourself saying, “I guess you had to be there” to the accompaniment of crickets chirping. “No @hit, there we were” stories rarely make good songs. But songs on general themes of chivalry and honor, or a king leaving the throne don’t need to be about one person to be meaningful. And songs about silly rules or bad feasts can go viral. O.o

If you must filk, please don’t filk modern songs, or SCA standards. The former can lead to lawsuits, and the latter is just bad manners unless you have the author’s permission. Don’t play with other people’s toys without asking. You can read my “Period Filk and Contrafacta” class notes online (https://www.ravenboymusic.com/period-filk/) for some other ideas.

“Do as I say, not as I do” on this one—I can’t tell you how many times I have thought “THERE’S a great idea for a song” and not bothered to write it down. Poof! Gone forever. Sometimes they come back, but the Muse can get bitchy about being ignored. Carry a little notebook with you whenever possible. My husband methodically wrote down descriptions of disgusting feast food for years until it became “The Feast Song.” There’s no way it would have been as funny if we had tried to remember all the awful things we cringed over. And if there’s even one image or bit of lyric (or tune), WRITE IT DOWN. Even if you don’t use it, it may turn out to be the starting point for a different piece entirely.

For those of you who make up tunes and don’t read music, you should learn, but until then there are several options for noting your tunes. A recording is the obvious one, and since a lot of people’s cell phones now take short videos with sound, you may have a recorder to hand. But if you at least know notes on some instrument, you can notate your melody by the letters. Here are the first lines of “Yankee Doodle” (in C–Capitals are middle C and above, lower case letters are below middle C):

C C D E C E D g C C D E C b / C C D E F E D C b g a b C C

If you know what the notes are, you don’t necessarily have to know where they belong on a staff. If you don’t have even that much music theory, you can at least make dots on a paper that shows where your tune goes up and down, which is sometimes enough to jog the memory. And make friends with someone who reads music!

Is it Original or Isn’t It?

People often ask me how they can be sure a tune they come up with is truly original, and not something they’ve heard at some point and half-forgotten. I tell them, “Welcome to the world of songwriting.” There is no one, and I mean NO ONE who does not go through this. On the DVD of Paul McCartney’s Good Evening New York, he talks about writing “Yesterday,” and it was so different from his usual work he was convinced he had heard it somewhere. He asked John, and the rest of the guys, as well as George Martin, and none of them found it familiar. It was many months before he believed it was original and felt he could record it. So if a prolific popular songwriter does not trust his own ear, or those of his band mates and producer, how neurotic do you think the rest of us are?

On the other side of the coin is George Harrison lamenting to his manager after they had recorded “My Sweet Lord” that he realized after the fact that the tune was pretty much made from “He’s So Fine” and wondering how much of a problem it was. It probably would have been none at all if he had not quarreled with and fired that manager, who promptly went out and bought the rights to “He’s So Fine” and sued Harrison.

Creation is a magical process. Suddenly there is a thing in front of you that wasn’t there before, and you can’t believe it came out of your head. In fact, it came out of the punchbowl (and hopefully you now know what I mean by that) and is made up of all the bits that have gone into the punchbowl. Harrison was judged guilty of “unconscious plagiarism.” He didn’t copy the song on purpose, but he also didn’t do what McCartney did, which was, ask a bunch of musically knowledgeable people he trusted to add their ears (and punchbowls) to his. My husband and I constantly ask each other if something we’re working on “sounds familiar.”

Often, I can pin a particular sequence of notes to a source, but if it’s a short enough sequence, it really doesn’t matter. There is no such thing as a sequence of notes that have never been strung together before. If you realize that you got a short sequence of notes from another song, don’t feel you have to throw them out, just recognize that your next line should be intentionally different from wherever you got the bit in the previous line. If you borrow the notes AND the words that go with them, you’re treading on thin legal ice. (There can be good reasons to borrow little bits of other works, and we’ll look at those in a minute.)

The more you pay attention to the emotional impact of certain sequences of notes, or of the juxtaposition of certain notes and certain chords, you’ll start to notice that parts of songs where the guy gets the girl sound a lot alike, as do the parts where the guy loses the girl. The writers aren’t really stealing; they’re simply using the same musical tricks to elicit the same emotional response in the listener. There is a particular emotional impact for any two notes played together, and composers have been making use of it since ancient times. Plato and Aristotle wrote about the emotional impact of melody, and John Dowland was still writing about it at the end of our period [2, 3, 4]. And prolific songwriters are still making money off it today.

If you are in doubt, there is no substitute for another ear, preferably one likely to know the same tunes you might have borrowed from. (If your advisor has never heard of Dougie MacLean, he’ll never recognize that you used a Dougie MacLean melody, and if they’ve never heard a Cantiga, they won’t pick up on that.) Find somebody with a decent memory for tunes whose punchbowl has a lot in common with yours. Ideally, you should ask while you’re working on a piece, rather than waiting until it’s a thing and then finding out it needs to be changed.

Creating a New Tune From an Old One

If you have never written a tune completely from scratch, it might be less intimidating to create a new tune from an existing melody. Consider it the middle ground between original work and contrafactum (or filk). I teach people a trick I like to call it “The Sesame Street™ Method for Avoiding Copyright Litigation”. If you have kids and have seen SS, you’ll know they often have songs that sound an awful lot like a popular song but not so much that they get sued.

My favorite Sesame Street “new tune” is a knock-off of “Can Do” (aka “I Got the Horse Right Here” or “Fugue for Tinhorns”) from Guys and Dolls, but they did it as “Can Read”. They did the overlapping melodic lines and fugue ending, but they inverted most of the lines. They didn’t use enough lyric or enough melody to be actionable…the letters above the words are the notes (Capitals are middle C and above, lower case are below middle C).

The original:

E a D g C f f e f b e

Can do, can do, this guy says the horse can do

Their version:

C A C G E D E F g G E

Can read, can read, a newspaper you can read

If you plunk that out on the piano, you’ll see that SS’s goes up where Frank Loesser went down and vice versa (they also played with the tempo in the middle of the line a bit). You end up with a piece where you can play the same basic musical accompaniment behind it, but you can’t call it the same tune. I mean, there’s nothing new under the sun, right? Every interval in the normal scale has been used many times, so you really have to string together a lot of notes before the lawyers call. And the only word that appears in both is “can.” People like to call this an “homage,” which is French for “we stole it, you know we stole it, but you’ll never win in court.”

Look at “Gilligan’s Island”:

E a E E E E D b g

Just sit right back and you’ll hear a tale

As a guitar player, I hear the line as Aminor and G; the same chords work if I change the tune to:

e a b C b a b C D

Just sit right back and you’ll hear a tale

Now if I change some words, hey presto, I have a new song! My melody is high where theirs is low, and moves where theirs holds steady. As long as I get rid of “Just sit right back”, you’ll probably never pick it out as being related to “Gilligan’s Island.” On the other hand, the pacing is very hornpipe-esque, (a dance and related tunes from the 17th century onward strongly associated with ships and the Navy) so you’ll probably feel like the song should be about a boat, but you won’t know why, bwa-ha-ha! This is an excellent reason to borrow bits. That old pattern recognition will kick into your listeners’ brains and they will make unconscious associations that (hopefully) support the style and mood you’re going for. Don’t work from Gilligan’s Island and write a lyric about people dying on the battlefield!

(Amusing factoid: there is a Playford dance called “Goddesses” that has a very similar melodic line, EaaCbabbD, and you’ll often hear SCA musicians who become bored by Verse 4 or so launch into “Gilligan’s Island” as a melodic counterpoint.)

The easiest way to begin is to work out the chords of the original You can do this on any chromatic instrument, that is, an instrument that plays both C and C#, such as a piano or guitar. WARNING: I am assuming in these steps that you know what a chord is. A chord is a group of notes played simultaneously to provide a fuller sound than a single note. It can also be used to emotionally color a melody; many chords contain a C note, and any can be played along with it, but the emotional feeling will be very different for each. A C chord (c-e-g-C) played while a C is sung will give a full, finished feel; an A minor chord (a-C-E-A) will have a dark, plaintive feel; an F chord (f-a-C-F) will have an unfinished, longing feel, etc. If this is beyond your musical understanding, you can still adapt the melody, but it had better be one you know VERY well because you won’t have an accompaniment to keep you on track.

Find the high and low points of the line, and go the other way to start your melody. Example: the E above middle C that begins the original melody is the highest note in the A minor chord when played on a guitar, so I went to one of the lowest notes in the chord, e below middle C as the start of my line. I then looked at that three note cascade in G: D-b-g and went the other way: b-C-D. Anything goes as long as it’s in the chord. Then find a pleasing set of notes to get you from point A to point B. Because of that long string of tones that stay on the same note, I chose to deliberately go up and down again. As long as it’s in the chord, you’re okay. The chord is your anchor.

Okay, what about those of you who don’t read music and don’t play an instrument? If your ear is good, you can probably feel your way into a compatible but different melodic line. Just keep singing the original melody, then yours, and make sure they sound different in a number of places. Then sing your tune for someone else and see if they recognize it. People were making up tunes long before they knew how to read music. Try something really simple that you know well, like “Happy Birthday” or “Row Your Boat.” Sing it, then sing around it. It will make your head hurt at first, but you’ll get the hang of it.

What if your ear stinks? Then it becomes a math problem. From any note, you’ll only have three or four reasonable choices of where to go next while staying within your range and not producing a melody that you can’t remember. (And if you use a pentatonic scale, you’ll have even fewer choices!) And if you’re trying NOT to do what the original tune does, that cuts out one of your choices. I could honestly program a computer to generate melodies (and I’m sure someone has). I can’t promise they would be good melodies, but I can say the same about a lot of pop music.

Even if you can’t read music or play properly, I highly recommend picking up a cheap electronic keyboard (heck, you can number or color-code the keys). Nothing will help you understand where to go like having the notes all laid out in a line. Start playing around with notes (preferably with a tape recorder running, because if you hit something really cool and don’t know what you did, you’ll be really mad!). Pick a note, any note, and be sure you keep coming back to that note to end most of your lines. That will keep you out of really awful trouble until you can brush up on some music theory.

Scary Theoretical Stuff: Chord Inversions

Basic chords begin and end with the root note, like a root-note sandwich. An inversion is to play a chord with the “wrong” note as the bread. A “standard” C chord is c-e-g-C; you make an inversion by playing it e-g-C-E or g-C-E-G. The combination of notes (C, E, and G) makes it a C chord regardless of what note is “on top”, but the ear perceives it differently. You can do the same thing with a melodic line by sticking to the same chord structure and choosing different notes from the same chord at key points in the line.

Depending on what your musical background is, you may find you invert chords naturally. I am a much better guitar player than I am a piano player (you can’t really call what I do “playing” the piano, but I know where all the notes are). Unlike the piano, where all the notes are laid out in a straight line, the guitar groups them together based on fingering positions on different strings, which often results in natural inversions. If I play a C chord on the middle four strings, I get c-e-g-C; if I play on the top four strings, I get e-g-C-E. I find I make very different melodic choices depending on whether the piano or a guitar (or nothing) is handy.

Scary Theoretical Stuff: Modes

Most period melodies are purely modal. Modes are just different scales from your standard do-re-mi. For someone with no music theory, the easiest modes to stick to are the two closest to modern major and minor scales: Ionian and Aeolian. Ionian is simply Do-re-mi-fa-sol-la-ti-do, or the white keys on a piano starting at C. You can go beyond the octave, that is, sing mi above ti and do, but you can’t go between, that is, sing “mi sharp” or “mi flat”. “Sumer is Icumen In,” the 13th c. popular hit, is written in Ionian mode with an 11-note range. (If your song is minor in tone, try Aeolian, which is La-ti-do-re-mi-fa-sol-la, or the white keys on a piano starting at A.) If you play your song in C and you need to hit F#, you’ve used an “accidental” or a note that doesn’t appear in the pure mode. (Shame on you.) Accidentals did exist in period, but they were rare and occurred at only a few places in the octave. (There’s one in “Greensleeves”.)

If all this mode business sounds fascinating and seductive, you can find the notes for my class on modes online at https://www.ravenboymusic.com/what-is-a-mode and delve deeper.

Not So Scary Theoretical Stuff: Range

Most period melodies have a small range. If you have a natural three-octave range, congratulations. It’s understandable to want to show that off, but early melodies didn’t cover that much ground. As I said above, “Sumer” has an 11-note range, not much over an octave. “Greensleeves” has a 10-note range, as does the popular Elizabethan bawdy song “Watkin’s Ale”. “Qui Creavit Coelum” (The Hymn of the Nuns of Chester, ca. 1425) has a 9-note range. Gregorian chant, including “Ut queant laxis” (The St. John Hymn, ca. 800 A.D.) typically kept to a six-note range [5]. Certainly, you will see court pieces designed to highlight virtuosity, and multi-part arrangements that use different ranges to hit a wide span of notes, but songs meant for many people to sing together, or for popular entertainment, would have had a limited range.

KNOW YOUR RANGE. If you are writing for yourself, don’t extend your melody to the point where you have to screech or bottom out. Writing your own material is a way to make yourself look good. Write to the “meat” of your range, where you have the best volume and tone.

Creating a New Lyric From an Old One

No, I’m not kidding, and no, this is not filk. If you have tunes dancing in your head from morn ‘til night but don’t have a clue how to begin a lyric, then as we did previously with the tune, try starting with something that already exists. Nothing is scarier than a blank page!

As I mentioned in the “idea” section, we can trace a clear lineage from Chaucer through Boccaccio back to at least Ovid, and there is undisputed evidence of source material for works by Shakespeare, Marlowe, and many other people we consider great writers. I love the fact that the Wikipedia entry for Christopher Marlowe calls him “an English dramatist, poet and translator…” The best writers are voracious readers, and that was true in period as well. Happily, many of our great English writers were educated enough to know several languages, and what a boon it is when you find a great story in French or Italian that you know most English readers can’t read? There is a literary term for this; if you ever see a lyric credited as “Pr. <author’s name>” it means “paraphrased”, meaning rather than being a direct translation, it is an approximate translation altered for poetic effect. Translated words rarely rhyme; what do you do with a French couplet that rhymes <mer> ‘sea’ with <fer> ‘iron’? At the end of these notes, you’ll find a stanza from Le Roman de la Rose along with a period English paraphrase and one I did. Mine is much closer to the French than the medieval one (and if you don’t read French, you’ll just have to take my word for that, bwa-ha-ha!).

So what if you are depressingly monolingual? There are many traditional ballads, epic poems, stories, sagas, etc. just begging to be edited. Our period forbears had much longer attention spans than we have. They didn’t work very hard to say in eight verses what they could say in two hundred. (I once knew a lady who could recite 45 minutes’ worth of “The Faerie Queene” from memory, but shockingly, there were very few people who wanted to sit for 45 minutes and listen to her…) There are some works, especially among the traditional ballads, which only exist in fragment. How about finishing (or filling in) the story? At https://aesopfables.com/ they have multiple versions of most of the fables, which are short, witty pieces of prose waiting to be fleshed out and versified. Whether you think your strength is expanding, reducing, or filling in the blanks, there are pieces out there waiting for you to transform them.

Still too hard for you? How about pop music? A friend in the East Kingdom wrote a fabulous sonnet. The more I read, the more my brain started to twitch. At last in the concluding couplet, she let it slip:

How vain thou art! I’ll wager this is true–

You doubtless think this sonnet’s about you.

She had taken Carly Simon’s “You’re So Vain” and turned it into a sonnet, apricot scarf and all. (It’s a fun exercise; you should try it sometime even if you don’t want to do anything with it.)

The further in style you can go from the original, the better. Take a sad song and give it a happy ending. Take a sappy song and kill everybody off. And with your own original tune, see if anyone picks up on it! Turn an essay into a poem, or a poem into an essay. The more you get used to bending words to your will, the more they will start spontaneously popping into your brain. Your punchbowl cannot be empty, or you wouldn’t want to write songs. Just keep stirring and adding ingredients until something speaks to you.

The True Usage of “Homage”

I was kidding when I suggested that homage is a kind of plagiarism. Strictly speaking, I guess it is, but it’s like naming a street after someone. You mean it as a compliment (just like in English, paying “homage” to someone). And, as we saw with using bits of melody and structure, you can pick up on mental associations that anyone who recognizes the borrowed bit, even unconsciously, will make. The same thing can happen with words. I was trolling through the Oxford Book of Carols and found a carol called “In the Town” (paraphrased from the medieval French carol “Nous Voici Dans la Ville” into English by Eleanor Farjeon, probably in the 1930s) with this verse:

My guests are rich men’s daughters

And sons, I’d have you know!

Seek out the poorer quarters

Where ragged people go.

Now consider Paul Simon’s “The Boxer”:

When I left my home and my family

I was no more than a boy

In the company of strangers

In the quiet of a railway station, running scared

Laying low, seeking out the poorer quarters

Where the ragged people go

Looking for the places only they would know.

With all due respect to an infinite number of monkeys, there is ZERO chance that Paul Simon did not see Eleanor Farjeon’s work. But this is a perfect example of an “homage”-sized clip. I’m sure Paul Simon read Farjeon’s poem and thought “THAT is a cool turn of phrase; I’ve got to use that.” From a strict literary perspective, this is exactly what an homage is supposed to do for you—add emotional color or connotation. Anyone who did recognize the phrase would gain the association of Simon’s main character finding nowhere safe to sleep, with Mary and Joseph being told there was no room at the inn.

You can usually accomplish your goal with very few words, and the more well-known something is, the fewer words you need. The art is trying to use few enough words and subtly enough that the listener either gets the point subliminally, or gets the joy of working it out. You can say “green sleeves” if you are trying to bring that piece to the listener’s mind, but you might as well hit them with a brick. “Alas, my love” will also do the job, but is probably still too overt. How about “delighting in thy company” or “vouchsafe to love me”? It is much cooler to honor a well-known SCA song with “I was raised in the wars” or “My mother’s child” than the line everybody would expect.

When you aren’t trying to borrow bits because they are cool, you can still borrow all those emotional associations by the use of allusion, or referring to a well known thing, person, or character. You know what you mean when you call someone a Judas or a Jezebel, and so does everybody else. And when you’re trying to get more meaning into fewer syllables, replacing “person who pretends to be my friend but stabs me in the back” with Judas is a real boon.

Connotation and Word Economy

Like allusions, many common words also come with emotional baggage. When you choose a word, you get two things: the denotation of the word, and the connotation of the word. Denotation is what the word literally and simply means; connotation is all the other stuff that comes with it. For example, what does “dog” mean, or denote? It just means dog. You don’t get anything with it except the identification with something canine. Of course, if you have alerted the reader with the surrounding words, you can change the denotation. If you say, “That guy is a dog,” the reader knows that guy doesn’t have four legs and a tail, but is somehow lacking in either the looks or the fidelity department. Using slang accomplishes a complete shift of denotation, but be very sure that every member of your audience is familiar with the slang usage. Otherwise they’ll start thinking your piece is about werewolves.

But back to describing canines. Choose “mastiff” and now you have “great big dog.” “Pup” gets you “young dog.” But what if you pick “cur”? It still means dog, but now you have the idea of “a mangy cur”, i.e. a dog that is ugly, starved, possibly mean, possibly mad or rabid. You’ve replaced a whole line’s worth of words by selecting a very particular single word. This is a huge boon in poetry and songwriting, where you’re looking to get the most bang from your syllabic buck. On the other hand, it can get you in trouble. If you pick a word from a thesaurus just because it rhymes, and you ignore (or simply don’t know) the connotations associated with it, you’ll totally confuse the reader:

A princess with a coat of fur

A lovely poodle, little cur

Huh? Sure “cur” rhymes with “fur”, but the lines are complimentary until it goes south with “cur”, which has a negative connotation. This could be intentional, to follow with:

What shame to shoe a doggie’s feet

When children cry for bread to eat?

There, “cur” alerts the reader that despite the opening, the poet rather detests the dog (or at least its owner). You can imagine performing this piece, placing a pause after “poodle” and letting your voice become angry with “little cur” and riding that anger into the next couplet. The use of “cur” provides a sudden emotional turn that can be very effective. But if you intended a fluff piece about your pet poodle, you wouldn’t want “cur”.

The other connotation problem is in combination. Intentionally odd combinations are known as “oxymorons”, like “thunderous silence” or “sweet agony”, and they serve a useful purpose, but you need to avoid UNintentional ones. Anytime you fuse two words as a unit, they should either make sense together, or they should form an obvious ironic opposite such that a reader can easily grasp your diabolically clever meaning behind their juxtaposition.

I absolutely encourage any wordsmith to make frequent use of a thesaurus and a rhyming dictionary, but “don’t use big words you don’t understand,” even if they are three letters long. Be sure you understand the word completely before you choose it.

Voice

What I mean by “voice” is the identity of the speaker of your lyric. Even if your lyric isn’t written in the first person, e.g. “As I was a-walking…,” there is a supposition about who is telling the story. Think about your speaker, and imagine your words coming from his or her mouth. Your words should be very different if your speaker or main character is a miller compared with the speaker being a king.

We in the modern world are generally more educated than a common person in the medieval period would have been, and since we have had English teachers drumming things like simile and metaphor into our heads, we tend to use them, even if we are writing the lament of a peasant girl who wouldn’t know a metaphor if one walked up and bit her. I can nearly always spot songs that purport to be traditional but aren’t by their word choice. Invariably, the writer will seize upon a cool image or word choice that would never survive the folk process of transmission through many often uneducated mouths.

Consider for example the word sylvan, ‘of the wood.’ It’s a lovely choice for a late-sixteenth century courtly sonnet, but for your song about Robin Hood, it’s completely wrong. (Word geek stuff: among other reasons, the adjectival use of the word is not earlier than the sixteenth century and follows the use of the word as a noun, meaning a wood nymph.) There is no way that someone who had not had a formal education in Latin would know the word at all, let alone use it to describe men living rough in the forest.

Read some of the sections of “A Midsummer Night’s Dream” and look at the drastic change in language between the classes of characters. There is a distinctly different level of erudition in language when Theseus speaks; Lysander’s lines are still educated but less lofty, and Bottom’s are downright common. You can mix up the scripts and still tell which you have, just by the quality of the language. Shakespeare really understood voice. Remember, though, that even if you have a king as a character, if the speaker is a common man, it’s unlikely even the king’s lines will be very lofty. It’s easier for an educated man to write dialog for a simple man than vice versa. If your storyteller is a potentially educated third party, you can put your best lines in the mouths of the educated characters and leave the common men to speak as they may.

The musical “Man of La Mancha” makes good use of voice; Don Quixote’s language is very flowery, while Sancho Panza’s is very simple, tending towards one-syllable words almost exclusively. Aldonza’s language changes noticeably from simple to complex over the course of the play as she is influenced by Don Quixote.

Voice is something that a lot of accomplished writers forget about completely, or choose to ignore. Sadly, preserving voice is sometimes at odds with other goals. You might have come up with a terrific allusion or elegant turn of phrase, but if the piece you’re writing is meant to be sung by a cottage woman waulking wool, would she know that word or understand that reference? You may have to choose between elegance of language and plausibility of voice.

I hope you’ve picked up some ideas that make you want to run for an instrument or a writing implement and get started writing your own songs. Feel free to drop me a line at lisatheriot@ravenboymusic.com if you have questions.

References

[1] I love the house metaphor. I got it, and quite a few other useful tips, from a fabulous book by prolific songwriter Jimmy Webb called Tunesmith (New York: Hyperion, 1998.) Though obviously aimed at modern songwriters, a lot of the advice is useful. Just remember our goals are different; in one exercise he lists words from a rhyming dictionary, and immediately throws out several because they sound archaic. I laughed, because those were the words I chose first!

[2] Plato, The Republic, book III, written ca. 360 B.C.E. features the following exchange, discussing musical modes:

And which are the soft or drinking harmonies?

The Ionian, he replied, and the Lydian; they are termed ‘relaxed.’

Well, and are these of any military use?

Quite the reverse, he replied; and if so the Dorian and the Phrygian are the only ones which you have left.

[3] Aristotle, Politics, Book 8, part v, written ca. 350 B.C.E. states (again discussing modes):

Some of them make men sad and grave, like the so-called Mixolydian, others enfeeble the mind, like the relaxed modes, another, again, produces a moderate and settled temper, which appears to be the peculiar effect of the Dorian; the Phrygian inspires enthusiasm.

[4] Dowland, John, Andreas Ornithoparcus his Micrologus, or introduction, containing the art of singing, published 1609, translation of the original published 1517, states:

The Dorian Moode is the bestower of wisdome, and causer of chastity. The Phrygian causeth wars, and enflameth fury. The Eolian doth appease the tempests of the minde, and when it hath appeased them, lulls them to sleep. The Lydian doth sharpen the wit of the dull, and doth make them that are burdened with earthly desires, to desire heavenly things…

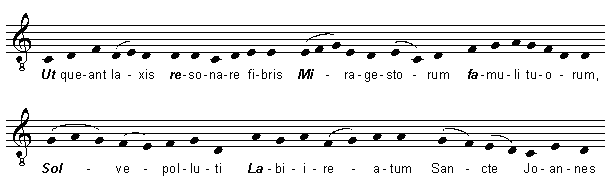

[5] Guido d’Arezzo, Micrologus, written ca. 1025-1028. For educational purposes of teaching sight singing, Guido d’Arezzo is credited with the invention of solfege (or solmization), referring to notes by name. He used the first syllables of every line of the “Saint John Hymn” (“Ut queant laxis” ca. 800 A.D.) and assigned them as singing syllables for each of the tones within the hexachord (first six notes) of the diatonic scale:

(“That these your servants may with all their voice, sing your marvelous exploits, clean the guilt from our stained lips, Saint John”.) The syllables of “solfege” remained ut-re-mi-fa-sol-la until 1673 when Giovanni Bononcini suggested a change from “ut” to “do” [6].

[6] Bononcini, Giovanni Maria, Il Musico prattico, published 1673 in Bologna. Bononcini reportedly chose “do” from “domine”. The application of the initials of Sancti Iohannes (“Saint John”–remember, in medieval Latin “I” and “J” are identical) to create “si” for the seventh is credited to Anselm of Flanders in the 16th century. In much of the world they still use “si” for the 7th; “ti” is strictly modern.

Other Websites You Should Know About

Choral Public Domain Library (ChoralWiki). Solo and choral arrangements organized by composer, most with midis.

Fordham University’s Internet Medieval Sourcebook. Medieval letters and documents organized by period and topic. Way cool.

https://www.fordham.edu/halsall/sbook2.html

Greg Lindahl has quite a few period pieces (and music) available online at his personal website. https://www.pbm.com/~lindahl/

Outlaws and Highwaymen. The author of a book by the same name has a great deal of her research material here, including original (un-spell-corrected!) text from the 1556 English translation of Thomas Mores Utopia. Also, not surprisingly, you’ll find good info for documenting outlaws and highwaymen, a favorite topic for SCA bards.

https://www.outlawsandhighwaymen.com/

Rhyme Zone. An online rhyming dictionary and thesaurus (any poet who says they don’t use a rhyming dictionary either lies or writes bad poetry). Best of all, there’s that search engine to the complete works of Shakespeare, allowing you to check for period word usage.

Sacred Texts Online. Okay, I know they have stuff on UFOs. But they also have all the Child Ballads, and good webbed translations (and a few originals, like Beowulf) of Arthurian, Celtic, and Norse works as well as studies thereon. Tiptoe through the trash and look for the treasure.

The University of Cork has a huge web-published collection of medieval Irish works in original and translation, which they call CELT: the Corpus of Electronic Texts. If you’re writing anything modeled on an Irish example, you have to know about this site:

The University of Michigan’s “Corpus of Middle English Prose and Verse” features un-edited versions of Malory’s Le Morte d’Arthur, Piers Plowman, Chaucer, and other gems.

https://www.hti.umich.edu/c/cme/

Appendix: Roman de la Rose

The original French opening (Guillaume de Loris, ca. 1230):

Où vintiesme an de mon aage

Où point qu’Amors prend le paage

Des jones gens, couchiez estoie

Une nuit, si cum je souloie,

Et me dormoie moult forment,

Si vi ung songe en mon dormant,

Qui moult fut biax, et moult me plot.

Mès onques riens où songe n’ot

Qui avenu trestout ne soit,

Si cum li songes recontoit.

The English paraphrase, Romaunt de la Rose (probably Chaucer, ca. 1380):

Within my twenty yere of age,

Whan that Lovt; taketh his corage

Of yonge folk, I wente sone

To bedde’ as I was wont to done,

And fast I y sleep ; and in sleping,

Me mette swiche a swevening,

That lykede me wonders wel;

But in that sweven is never a del

That it nis afterward befalle,

Right as this dreem wol telle \is alle.

My paraphrase (ca. 2009):

When I was twenty years of age,

The time when Cupid plays the page

To every youth, I lay my head

One night, as custom, in my bed,

And while I lay in slumber deep,

A dream came to me in my sleep

That in its beauty struck me sore.

I never knew a dream before

Or any since that I have known

That like this dream the truth hast shown.