Building Period-Sounding Melodies: a Simple Guide to Modes

(No, Really.)

by Adelaide de Beaumont (Lisa Theriot)

What is a Mode? Does it involve Ice Cream?

Sadly, no. A mode is nothing more or less than a scale. The modern major scale is identical to the mode known as Ionian. The modes, seven in all, are just different sets of notes by which to sing a diatonic, or “do-re-mi” type of scale.

Ancient Greek music referred to scales by scalar modes; each mode was named for a city that seemed to prefer that mode in its music. Plato and Aristotle believed that playing music in a particular mode would affect a person’s behavior; Plato suggested, for example, that soldiers should listen to music in Dorian mode to help make them stronger, and avoid music in Lydian mode, which might make them soft [1, 2]. This belief that the mode of a piece of music emotionally affected the listener persisted throughout our period [3].

The so-called “church modes” of medieval European music were descended from the idea of modality but had little actual correspondence with Greek modes. Boethius is credited with our use of the Greek terms; his famous 6th century treatise on music included an attempt to line up modes in use by the early church, generally referred to by number (I, II, etc.), with the ancient Greek modes [4]. Since the scales employed were totally different, this was roughly equivalent to trying to classify varieties of apple according to the characteristics of orange varieties. Be assured that what we’ll describe later as Lydian mode does not correspond exactly with what Plato would have described as the Lydian mode, so there’s no need to send the fighters out of the room when playing in it.

The Greek mode names came into common application for medieval music around the 10th century. The principal music theorist of the day, Guido d’Arezzo, described the practical application of four modes: Dorian, Phrygian, Lydian and Mixolydian [5]. (He also described four companion or “plagal” modes: Hypodorian, Hypophrygian, Hypolydian, and Hypomixolydian. These modes used the same notes with the same intervals, but began at a different point in the octave. They were originally used for building polyphony, which is beyond the scope of this class. We’ll be sticking to the so-called “authentic” modes.)

In 1547, the treatise “Dodekachordon” (“Twelve Strings”, “The Twelve-Stringed Lyre”) was published by Swiss theoritician Heinrich Glareanus. Glareanus attempted to close the gap between the officially recognized church modes and the way people were actually writing music. He recognized two more modes (okay, four– these had “hypo” forms just like Arezzo’s, and we’re not talking about these either): Ionian and Aeolian [6]. Not a moment too soon: the famous medieval hit “Sumer Is Icumen In”, written in the late 13th or early 14th century, is in Ionian mode. As usual, theory was lagging well behind practice. Glareanus also discussed a seventh set of “hypothetical modes” (now known as Locrian) but he dismissed them as virtually unusable.

By 1600, British popular music was dominated by the four modes nearest to our modern ideas of “major” and “minor”: Ionian, Dorian, Mixolydian and Aeolian [7]. Though accidentals, or variations from the pure mode, had started to creep in to composed music, traditional music remained almost purely modal [8].

So how does a modal scale differ from the standard do-re-mi?

Modern music speaks in terms of scales based on keys, and recognizes “major” and “minor” keys. A lot of modern music theory is based on specific frequencies, something that a medieval musician would have had trouble with. If you’re playing a hand-carved flute, your “C” might not be the same tone you’ll get from hitting middle C on a piano. So you have to describe your scale solely based on the relationship between the notes.

Most Western music is based on the diatonic scale. The Greeks cooked up the diatonic scale as a mathematical exercise, just as they did the dimensions of their architecture [9]. They used an instrument called a monochord, which you can think of as a one-stringed guitar. They stretched one string over a sounding box with a movable bridge and used the bridge to divide the string into a series of happy mathematical ratios, like 1:2, 3:2, etc. They settled on a series of notes between which they found pleasing relationships and created what we refer to as the “octave”, beginning with one note (later called the “tonic” or “finalis”). Pythagoras is generally credited with being the first to note that when you divided a string in a 2:1 ratio, you get the same note, but the note on the shorter portion of the string is much higher in pitch [10]. Six other notes were arrived at by application of ratios of which the Greeks were fond, and the eight-note octave was born.

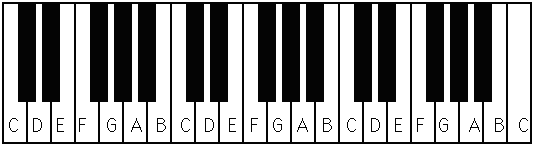

Because the chosen ratios weren’t related in a linear fashion, the Greeks discovered that the math required them to place tones between some of the notes of the diatonic scale, and thus created the 12-note chromatic scale with half tones between the 1st and 2nd, 2nd and 3rd, 4th and 5th, 5th and 6th, and 6th and 7th notes [11]. The modern C-major scale, using only the white keys on the piano, can be described by the distance between the notes as W-W-H-W-W-W-H where W indicates a whole note jump and H is a half note jump: C(whole)D(whole)E(half)F(whole)G(whole)A(whole)B(half)C. The best visual clue for this relationship is again on the piano; notice there is no black key between E and F or between B and C:

We’re going to be playing on only the white keys with the method outlined below, but fear not if the resulting key isn’t in your range; the rules work in any key. (For tips on transposing to another key, see Appendix II: The Chords in C Major.)

We’ve already mentioned that the notes of the C-major scale (or any major scale, for that matter) correspond exactly to the mode called “Ionian”. Any melody for which C is the tonic, or root note, that can be played entirely on white keys is written in Ionian mode. The do-re-mi with which we are all familiar is the Ionian scale (and in fact “Doe, a Deer” from “The Sound of Music” is an Ionian melody).

The intervals for Dorian mode are shifted; Dorian can be written as W-H-W-W-W-H-W. Happily, this is just shifted one key down on the piano, so if you begin on D instead of C and play only white keys you will play a perfect Dorian scale. Of course, you can play them all starting on C, but you need those nasty black keys. If you’d like to see what they all look like in C, go to Appendix I: The Modes on C at the end of these notes. Likewise, you can play all the modes in any key; since Ionian is identical with the major scale, G Ionian is G-A-B-C-D-E-F#-G. But there are those black keys again. (If you are very clever, Grasshopper, you may eventually notice that modes and keys are related in the number of sharps and flats naturally occurring in each major key, but that is way beyond the scope of this class.) Our goal is to make this as easy as possible, so today we spurn the black keys.

Playing the white keys on a piano gets you a perfect modal scale from the tonic as follows:

| 1st | C | Ionian mode | W-W-H-W-W-W-H | major mode | |

| 2nd | D | Dorian mode | W-H-W-W-W-H-W | minor mode | church mode I |

| 3rd | E | Phrygian mode | H-W-W-W-H-W-W | minor mode | church mode III |

| 4th | F | Lydian mode | W-W-W-H-W-W-H | major mode | church mode V |

| 5th | G | Mixolydian mode | W-W-H-W-W-H-W | major mode | church mode VII |

| 6th | A | Aeolian mode | W-H-W-W-H-W-W | minor mode | |

| 7th | B | Locrian mode | H-W-W-H-W-W-W | minor mode | |

| . |

The ordinal (1st, 2nd, etc.) indicates the relative position of that note to the tonic or finalis. When C is my finalis, or the opening note of my scale, and I talk about the “4th” I mean F, “7th” means B, etc. (These notes all have names, often many names; if you’re interested, they include, respectively: 1st, finalis or tonic; 2nd, supertonic; 3rd, mediant; 4th, subdominant; 5th, dominant or “tenor”; 6th, submediant dominant; and 7th, leading tone. These names are nothing like standard throughout the world or throughout history, so referring to them by number saves a lot of grief.) Yes, they’ll all change when we shift modes. In “white key” Dorian, D will be our finalis, A will be the 5th; in “white key” Aeolian, A will be our finalis, E our 5th, etc. Hey, if there weren’t some work involved, everyone would do it.

You’ll notice I’ve marked the modes as “major” and “minor”. Ionian mode is what we now think of as standard “major”, and Aeolian is generally considered standard “minor”, but all modes have a flavor, or tendency towards the upbeat or downbeat. Later, when we’re considering examples of modal melodies, you’ll see what I mean.

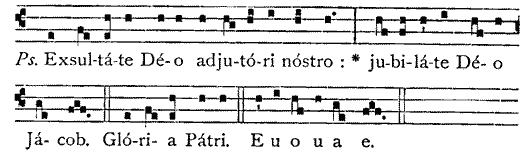

The “church modes” are also called Gregorian or chant modes. Chant music frequently identifies the mode by Roman numeral (note only the odd numbers appear—the even numbers are assigned to the plagal modes like Hypodorian, etc.).

So if do-re-mi describes Ionian, it must be 16th century or later, right?

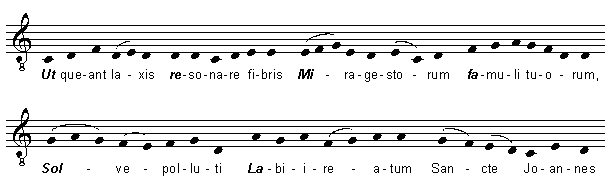

Not exactly. Good old Guido d’Arezzo is responsible for do-re-mi, though it began as ut-re-mi: For educational purposes of teaching sight singing, Guido d’Arezzo is credited with the invention of solfege (or solmization), referring to notes by name. He used the first syllables of every line of the “Saint John Hymn” and assigned them as singing syllables for each of the tones within the hexachord (first six notes) of the diatonic scale:

St. John Hymn, “Ut queant laxis” ca. 800 A.D.

(Before you ask, it means “That these your servants may with all their voice, sing your marvelous exploits, clean the guilt from our stained lips, Saint John”.) The syllables of “solfege” remained ut-re-mi-fa-sol-la until 1673 when Giovanni Bononcini suggested a change from “ut” to “do” [12].

You told me do-re-mi is Ionian! Guido didn’t talk about Ionian! And why does it only go to La?

Actually, the hymn is Mixolydian, church mode VII. In Arezzo’s day, they really didn’t like octaves. There was an oddly superstitious hatred of the B, or natural 7th, by church musicians, so they built their melodies on “hexachords”, or six-note combinations. Most Gregorian chant is hexachordal; you’ll rarely find a 7th. If we clip off the last two intervals from our chart above to reflect only six notes, we get:

| C | Ionian mode | W-W-H-W-W |

| D | Dorian mode | W-H-W-W-W |

| E | Phrygian | H-W-W-W-H |

| F | Lydian mode | W-W-W-H-W |

| G | Mixolydian mode | W-W-H-W-W |

| A | Aeolian mode | W-H-W-W-H |

| B | Locrian mode | H-W-W-H-W |

| . |

Notice that Ionian and Mixolydian are now identical? The difference between the modes occurs at the 7th, so if we ignore the 7th, there is no difference. So ut-re-mi written in Mixolydian flows naturally into the modern Ionian usage.

So how does this help me write a period-sounding melody?

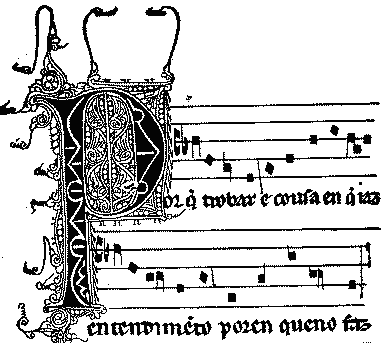

The overwhelming majority of medieval music, both religious and secular, is purely modal. There are a few examples of accidentals and mixed modes, but they are generally rare (don’t worry, we’ll talk about accidentals and mixed modes later). So if your goal is to write a period-sounding melody, you should be thinking about staying within the bounds of a single mode, and that is remarkably easy. Stick to the white keys. If you want to write especially old-sounding melodies, start from D, E, F, or G and you’ll fall naturally into the oldest modes. Try sticking to hexachords and you can write your own Gregorian chants.

So any tune I start on D using only white keys will be Dorian?

If it were quite that easy, you wouldn’t need a class. It’s helpful, at least at first, to begin and end your melody on the finalis, so if you want Dorian, that’s D. Play a short series of notes and come back to D. It’s almost impossible that your tune isn’t Dorian. Let’s look at this sequence:

D-F-G-A-G, F-G-F-E-D

(Here I’ve divided two short musical phrases with a comma.) If you’re not sure you’re squarely within your mode, here’s a good test. We’re going to put a rudimentary arrangement to the melody. The most basic form of a chord is to play the 1st and the 5th tones of your scale (remember, the 5th is called the dominant or “tenor”—guess which vocal section usually starts on this note?). Here, that’s D (1st) and A (5th). This is a rough D chord, and it works equally well for major or minor. Play D and A simultaneously, and at the same time play your melody. Does it sound reasonably pleasant? Then you’ve stayed in mode.

Warning: this paragraph is a hair more advanced. If it makes your head hurt, skip it. You probably hear a little tension in the second half of the line; though the D-A “chord” works, it doesn’t sound quite right. This is how you begin to arrange a melody. Since the second phrase of music begins in F, try using F as your 1st and play F-C (a rough F chord). Sound better? Just as a test, use F as your 5th and play B-F. Blecch! The F-C works until the end of the line where you should hear tension again, leading you back to D-A. That’s because we went back to our finalis.

I strongly recommend that until you get accustomed to working within a mode, you stick to beginning and ending your melodies with the finalis, and don’t stray too far from it. It’s easy to accidentally find yourself drifting into another mode because you lost mental track of your starting point. Later, you can practice starting with the tenor, and from there you can go anywhere you want.

I have a good ear. Can’t I start my melody somewhere other than the finalis?

Sure. Many pieces start somewhere else, though most end up on the finalis (hence the name). If you’ve played or sung for awhile, you can probably hear the underlying finalis in a melody regardless of whether you’re ever hitting it. If you can’t, try playing the 1st-5th chord and see if it works. Note: If the melody is modern and it starts on something bizarre like the 7th or the 2nd above the octave, you won’t get a good result. Try singing the last note in the song and playing 1st-5th. Finalis, remember? If you can’t figure it out from the beginning, try the end.

Let’s look at the first line of “Silent Night” as an example. It’s Ionian, so our finalis is C, yet the notes are G-A-G-E, G-A-G-E. Playing our rough C using the 1st and 5th gives us C-G; that sounds nice with the G note, and in fact with the whole line. Now try the last line (“Sleep in heavenly peace”), C-G-E-G-F-D-C. Hey! Not only does that work while playing C-G, but we end on C, our finalis. (Yes, I know, the other lines aren’t so easy; it is a modern melody after all.) Note G is the tenor note; you’ll find a lot of melodies begin on the tenor note.

What about a note other than the finalis or the tenor? Let’s try a little experiment. The 1st-5th rough chord includes the finalis and the tenor, so we can assume that those notes work with it. Let’s try the others:

2nd, C-D-G: Well, it sounds nice, but it feels like you want to go somewhere, doesn’t it?

3rd, C-E-G: Ahhhh. That’s where I wanted to go. Welcome to the actual C major chord. “Barbara Allen”, an Ionian melody, starts on E (and ends on C).

4th, C-F-G: Again, sounds nice, but rather like we want to slip back down to that comfortable E.

6th, C-G-A: Probably the least comfortable combination in Ionian. Sounds like you just missed something (you did, the tenor). (If it sounds familiar, think about the chord at the end of the Beatles’ “She Loves You”.)

7th, C-G-B: Okay, but oh please don’t leave me there! Now you see why the 7th is called the “leading tone”; it’s grabbing you by the earlobe and dragging you towards the high C.

If, after trying every possible combination you still can’t hear which finalis/tenor combo supports your note, I’m afraid you’re stuck starting on the finalis. If your ear isn’t good enough to keep you out of trouble, only math will save you.

Can I use this trick to find out what mode my favorite song is in?

Of course. Just determine the finalis by trying some 1st-5th combinations as above and start playing the song using C where the finalis belongs. If you can play it on all white notes, it’s Ionian. No? Try D. If you hit all white notes, it’s Dorian, etc. If you know the song is in a major key, start with Ionian and then try Mixolydian if Ionian doesn’t work. If you know it’s in a minor key, try Aeolian, then Dorian if Aeolian doesn’t work. You can try this at home with several common examples:

Ionian mode: Most upbeat songs you know. “Yellow Rose of Texas”, “Silent Night”, “Adeste Fidelis”, “Dona Nobis Pacem”, “Barbara Allen”

Dorian mode: “Scarborough Faire”, “What Shall We Do with the Drunken Sailor”, “Sovay”

Phrygian mode: A lot of Latin music, especially flamenco, and a lot of Middle Eastern music. Try playing the typical flamenco trill that you hear in ads and spaghetti Westerns: E-F-E-D-E

Lydian mode: The themes from both “The Jetsons” and “The Simpsons”. Really.

Mixolydian mode: “The Great Silkie”, “The Minstrel Boy” (but only as played by pipe bands and traditional musicians—MB has been “converted” to Ionian by most people), “In Paradisum”

Aeolian mode: “The Wraggle-Taggle Gypsies”, “Dona”, “Gaudete”

Locrian mode: Locrian is incredibly rare in songs, especially in Britain and America. You’ll hear it occasionally in the score for scary movies because it’s so unsettling.

Notice in “Dona”, for example, that the chorus suddenly feels very “major” though the verse was very “minor”. No mode is entirely one or the other, and you’ll be surprised at the notes you can put in your modal tune without breaking the rules.

What if it works on more than one note?

Sometimes it does. As we already saw, if you don’t use the 7th, Ionian and Mixolydian are identical, so melodies that don’t use a 7th can be considered either or both, like “This Old Man”, “Frère Jacques”, “Twinkle, Twinkle Little Star” and “London Bridge is Falling Down”. The same is true of many mode VII Gregorian chants, like the one still used in Catholic services to sing the “Our Father”.

A similar relationship exists between the Dorian and Aeolian modes, though they differ at the 6th. The common melody to the ballad “Geordie” doesn’t use the 6th, so it’s impossible to say which mode applies. The same is true of “Trees They Do Grow High”, “Bedlam Boys”, and the round “Rose”. (On a personal note, I discovered after the fact that this is true of a several songs I’ve written. If you listen to enough traditional music, it gets into your head so far that it becomes intuitive. Modal in, modal out.)

You can see why Ionian and Aeolian weren’t considered necessary for a long time; since many older major melodies tended to avoid the 7th and many older minor melodies tended to avoid the 6th, Mixolydian and Dorian were sufficient to explain most melodies.

What if I can’t play all on white keys when I start from any note?

There are several explanations. Many modern melodies, and even a few period melodies, include notes referred to as “accidentals”. Accidentals are notes used either sharped or flatted when the natural note has already been used (or is the expected note for the mode of the song). A common modern example is the American tune to “O Little Town of Bethlehem”: the opening line “O little town…” is sung (in C major) as E-E-E-Eb. You can’t have both E and Eb in any natural mode. There is no pure scale in which you can get that interval without an accidental. The fact that so many people seem to channel Mel Torme when they sing that line should give you a clue that it’s not a very period thing to do. Never say never (okay, there’s one in “Greensleeves”), but in general you should avoid accidentals. You know how they call it an “accident” when a child wets its pants? Think of accidentals the same way. If you must have an accidental, the most common place for one is at the 7th, like you’ll find in “Greensleeves”.

Another phenomenon is the “mixed mode”, which is just what it sounds like, namely using features of more than one mode in the same song. Many modern “minor” keys are played as mixed modes. Though Aeolian mode (W-H-W-W-H-W-W) is considered “true” minor, a minor key is sometimes played W-H-W-W-W-W-H, which looks like you stuck the front half of an Aeolian scale onto the back half of an Ionian scale. Probably not the most period thing to do, but I wouldn’t bet there are no period examples anywhere. Note: you may see period tunes identified as being “mixed mode”, but they are generally referring to using characteristics of both the authentic mode and its plagal mode, like Dorian and Hypodorian. Using the “white key” method, you’ll only notice that such a song is Dorian.

The third possibility is the key change. Some songs change keys, or modes, within the song. The “dramatic effect” key change at the end of a song (à la Barry Manilow) is pretty evident to the ear, but less so an internal mode change. The Beatles’ “Norwegian Wood” is Mixolydian in the verses but Aeolian in the bridge section. Again, I don’t know of any period examples, but I wouldn’t bet my life it was never done.

So now what do I do?

Go home and play on the white keys. If you don’t have access to a piano, get a cheap Radio Shack electronic keyboard. I’m talking about the 4-octave roughly 49-key boards; you don’t need a full 88-key board. If you can’t stand the thought of composing on such a modern instrument, you can use the same method on any diatonic instrument. A harp with no sharping levers is perfect. If there aren’t any “black keys” you won’t even be tempted to throw in accidentals. You need an instrument with at least a two-octave range, so unfortunately that lets out a recorder or period flute.

The goal is to make this as easy as possible (right?). So get ye to a set of white keys. With a little practice you’ll be cranking out perfect modal melodies with remarkably little effort.

[1] Plato, The Republic, book III, written ca. 360 B.C.E. features the following exchange:

And which are the soft or drinking harmonies?

The Ionian, he replied, and the Lydian; they are termed ‘relaxed.’

Well, and are these of any military use?

Quite the reverse, he replied; and if so the Dorian and the Phrygian are the only ones which you have left.

[2] Aristotle, Politics, Book 8, part v, written ca. 350 B.C.E. states:

Some of them make men sad and grave, like the so-called Mixolydian, others enfeeble the mind, like the relaxed modes, another, again, produces a moderate and settled temper, which appears to be the peculiar effect of the Dorian; the Phrygian inspires enthusiasm.

[3] Dowland, John, Andreas Ornithoparcus his Micrologus, or introduction, containing the art of singing, published 1609, translation of the original published 1517, states:

The Dorian Moode is the bestower of wisdome, and causer of chastity. The Phrygian causeth wars, and enflameth fury. The Eolian doth appease the tempests of the minde, and when it hath appeased them, lulls them to sleep. The Lydian doth sharpen the wit of the dull, and doth make them that are burdened with earthly desires, to desire heavenly things…

[4] Boethius, De institutione musica, written ca. 500 A.D.

[5] Guido d’Arezzo, Micrologus, written ca. 1025-1028.

[6] Glareanus, Henricus Loritus, Dodekachordon, published 1547 in Basel. Glareanus dismissed his “hypothetical modes” using B as tonic or finalis as impractical since their scales cannot, like those of the other modes, be divided into a perfect fifth plus a perfect fourth, or the reverse. These are now known as the Locrian and Hypolocrian modes; Glareanus called them the Hyperaeolian and Hyperphrygian.

[7] Chappell, William, Old English Popular Music (a new edition, with a preface and notes and the earlier examples entirely revised by H. Ellis Wooldridge), New York, 1961 [originally published 1838].

[8] Bronson, Bertrand Harris. The Singing Tradition of Child’s Popular Ballads, paperback, Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1976. Of over 4000 traditional tunes Bronson analyzed, less than 5% had accidentals, and the bulk of those were inflected 7ths. A good example of an inflected 7th is the tune to “Greensleeves”, which is typically played in either Aeolian or Dorian mode with an inflected 7th. The melody goes to the natural 7th on the word “wrong”, but the sharped 7th on “off” and “discourteously”.

[9] Aristoxenus of Tarantum, Harmonic Elements I, circa 4th century B.C., said about the origin of the diatonic scale: “We can establish that the diatonic is the first (proton) and the oldest (presbyteron); this is the type that the human voice naturally finds”. Interesting that the human voice in other parts of the world “naturally” found other scales, huh? Those crazy Greeks!

[10] Pythagoras unfortunately didn’t write about his findings; they first appeared in a work dating from around 300 BC called Division of the Canon and attributed to Euclid.

[11] The Greeks, in preferring the perfection of math over music, actually produced a chromatic scale that made it difficult if not impossible for unlike instruments to play together. In 1558, Gioseffo Zarlino published Le institutioni harmoniche “The Harmonic Foundations”. He complained that playing under the strict Pythagorean ratios meant that musicians were often out of tune with one another, and proposed some minor adjustments. He also detailed the plans for a chromatic instrument featuring what he called “just intonation” and produced a keyboard instrument functionally identical to the modern piano.

[12] Bononcini, Giovanni Maria, Il Musico prattico, published 1673 in Bologna. Bononcini reportedly chose “do” from “domine”. The application of the initials of Sancti Iohannes (“Saint John”–remember, in medieval Latin “I” and “J” are identical) to create “si” for the seventh is credited to Anselm of Flanders in the 16th century. In much of the world they still use “si” for the 7th; “ti” is strictly modern.

Appendix I: The modes on C

Invariably, somebody asks for a “translation” of the modes so that they all start on C. It is probably easier to hear the similarities and differences if you start on the same note, so here they are:

| Ionian mode | W-W-H-W-W-W-H | C-D-E-F-G-A-B-C |

| Dorian mode | W-H-W-W-W-H-W | C-D-Eb-F-G-A-Bb-C |

| Phrygian | H-W-W-W-H-W-W | C-Db-Eb-F-G-Ab-Bb-C |

| Lydian mode | W-W-W-H-W-W-H | C-D-E-F#-G-A-B-C |

| Mixolydian mode | W-W-H-W-W-H-W | C-D-E-F-G-A-Bb-C |

| Aeolian mode | W-H-W-W-H-W-W | C-D-Eb-F-G-Ab-Bb-C |

| Locrian mode | H-W-W-H-W-W-W | C-Db-Eb-F-Gb-Ab-Bb-C |

Appendix II: The Chords in C Major

Often, people ask how they can arrange or put chords to a modal melody. If you’ve written it using the white keys, you should start with the natural “white key” chords. Chords are generally built from the 1st, 3rd, and 5th tones in an octave; C major consists of C-E-G. Here are the other natural “white key” chords:

| C | major | C-E-G |

| D | minor | D-F-A (D major is D-F#-A) |

| E | minor | E-G-B (E major is E-G#-B) |

| F | major | F-A-C |

| G | major | G-B-D |

| A | minor | A-C-E (A major is A-C#-E) |

| B | diminished | B-D-F (B major is B-D#-F#, B minor is B-D-F#) |

| . |

If you have a more complex musical “vision”, you’ll want to branch out from these. Once you determine the most common chord in your melody, you’ll probably want additional related chords from the “family” of that chord. (I apologize for all the repeated quote marks, but neither “white key” nor “family” is a term that most musicians would recognize; I want to be sure that you’re clear that I’m using them only for purposes of this class.) You’ll pretty much have to determine which chords work by trial and error. You’ll also want to be familiar with chords related to the other major keys in case you need to transpose. Major keys work best for Ionian and Mixolydian, but they’re a good starting point whichever mode you choose:

| Major | Fourth | Fifth | Minor (6th) | Minor (2nd) |

| C | F | G | Am | Dm |

| D | G | A | Bm | Em |

| E | A | B | C#m | F#m |

| F | Bb | C | Dm | Gm |

| G | C | D | Em | Am |

| A | D | E | F#m | Bm |

| B | E | F# | G#m | C#m |

So if you come up with a melody in Ionian and you determine the chords should be C, Am, and F, but you need to sing it in G, your chords will be G, Em, and C, respectively.

Warning: if chords scare you, skip this paragraph! For example, I wrote a minor song and skipped the 6th, which means the song is compatible with both the Dorian and Aeolian scales. Since “white key” Dorian starts with D and “white key” Aeolian starts with A, I’m going to look at the “white key” chords PLUS the D “family” and the A “family”. Lo and behold, the chords for the song are: Am, G, D, E, C, and A. (I can play the whole thing just using only Am, Em, and G, natural “white key” chords, but I like the overtones I get from the chords I chose.) I wrote a song in Mixolydian; the chords are G, F, C, and Bb. I could have used F in place of the Bb, but again I liked the sound of Bb, and it’s in the F “family”, so it’s a fairly natural choice. If you find a “white key” chord that works, but the sound just isn’t quite right, try other chords in the “family” of that chord.

This is extremely brief, but any basic theory book, including things like “Learn to Play the Guitar in Five Minutes a Day” should have a complete chord chart to help you.