(Finding and Fixing a Repertoire)

by Adelaide de Beaumont (Lisa Theriot)

I have been in the SCA since the Stone Age (okay, A.S. XIII), and I have spent way too much money on hard-to-find books in order to at least make a stab at doing basic research. Thanks to the internet, that isn’t necessary anymore. There are huge collections of words and music available online. The problem these days is in knowing where to start, because there is just SO much material. And just as important, often, as where to look, is HOW to look. I’ll periodically post a big WARNING to let you know that even sources with great information can have dangerous pitfalls for researchers.

How you approach research is going to be somewhat different based on whether you plan to perform existing material or create original material based on historical models. For the very beginning bard, though, it’s often less scary to start with something other than nothing.

Is This Song Period?

I came into the early SCA bardic world with a huge advantage, because I had older siblings who listened to 60s-era folk music, which I picked up. At least 95% of it isn’t “period” when your benchmark is pre-1600, but a lot of it is at least traditional, based on themes and often plot/story elements that can be traced back to the medieval world. That’s better than a lot of people are doing in the bardic authenticity department. There is nothing wrong with singing songs you know in your first bardic forays. You should avoid pop songs, and any mentions of very modern topics, because it jars people out of the medieval mood. Eventually, you’ll get an idea of what other people are performing, and it will probably occur to you to look at the songs you know a little harder. Just asking the question of whether a song is appropriate in an SCA setting means you are past the “I like this song, and I’m going to sing it” stage, and have taken your first step on the bardic research ladder.

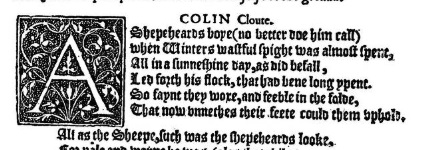

Here is a sad fact: Any song, story, or poem that looks and sounds normal to you isn’t period, at least in the version you have. It can’t be. Does your conversation sound like Shakespeare? I bet not, because most of us speak a version of modern English which simply didn’t exist by 1600. Here’s a stanza from Edmund Spenser’s Shepherd’s Calendar, published 1579 [1]:

A Shepeheards boye (no better doe him call)

when Winters wastful spight was almost spent,

All in a sunneshine day, as did befall,

Led forth his flock, that had bene long ypent.

So faynt they woxe, and feeble in the folde,

That now vnnethes their feete could them vphold.

Look at that spelling, and the language. “Ypent” is a Middle English holdover; we say “penned” now, putting the letters that mark the past tense at the end, rather than the beginning. “Woxe” here is the past tense of “wax”, so the sheep are “waxing faint” from lack of exercise. “Vnnethes” is found in Shakespeare as “uneath”, meaning ‘uneasily’. And this is 21 short years from the end of our period. Most performers opt for modern English, because that’s what our audience can understand without subtitles, footnotes, or a great deal of explanation. But making that choice doesn’t mean that it isn’t really cool to learn what the same piece looked like in period, assuming it existed, or to get closer to that language and further from how we speak in the modern world.

WARNING! MOST things you will find online have been “normalized” to modern speech and spelling, and a lot of them will still show you the original publication date. Horribly, even seeing misspelled words doesn’t guarantee you original text, because editors often “fix” the words they recognize, and leave the rest, so you can find the line “So faint they woxe, and feeble in the fold” online. Pro Tip: Look for a common word misspelled, like “feete”, or something capitalized for no reason (late-period printers, including those who printed Shakespeare’s earliest works, tended to capitalize personified nouns, here Shepeheard and Winter). Once you have even a small section of original text, you can put it in quotes and easily search for it without getting thousands of hits that don’t interest you.

This is a good place to introduce the concept of primary, secondary, and tertiary research sources. A primary source is a thing that existed before 1600; for our purposes, that will be a hand-written manuscript or an original printing, or at least a picture of it. There are many museums and libraries that have made items from their collections available online, and more appear daily, so if you can’t find something one day, it’s worth making a note and looking again in 2-3 months. Secondary sources are transcriptions of primary sources. If that’s all you can get, it’s better than a modern printing, but you have to trust that the transcriber correctly transcribed all the letters and didn’t decide to helpfully fix the charming anachronisms of spelling, punctuation, and sometimes grammar of the original. Also, carefully note WHERE they transcribed from, because if it wasn’t from a primary source, then they are actually a tertiary source, a copy of a copy. How does this change things? Here is the primary source for the Shepheardes Calender [2]:

This is a picture of the John C. Nimmo facsimile (London, 1890) of the British Museum copy of the first edition of 1579, so it isn’t as primary as we’d like, but photographic copies, rather than transcriptions made by humans, are generally accepted as primary. Yeah, that’s hard to read; this type is referred to as “black-letter” and a lot of printed primary sources look like this. You’ll get used to it.

My transcription above is from an 1869 work (so I know it was transcribed from THE original, because the facsimile didn’t exist) wherein the editor says, “In the present edition of Edmund Spenser’s works, no attempt has been made… to modernize the Poet’s language… I have been simply content to reprint the earliest known editions of Spenser’s various poems, correcting here and there some few errors that have crept into them by a careful collation with subsequent editions, most of which were published in the lifetime of the poet.” Yes, this guy caught a mistake between a 1591 printing and EVERY later edition (because editions copied other editions and didn’t go back to the source!) and fixed it. Mr. Morris, should we ever meet in Heaven, I will be proud to shake your hand. Sadly, this attitude was rarer than it should have been with the Victorians, so when you find a good one, it is cause for celebration. The same is true for works sourcing out of universities. Anything from Oxford, Cambridge, Princeton, Harvard, etc. is probably sound scholarly work. But as we say in our house, “Trust but verify.” You find outright error in the most depressing of places.

The lovely “Renascense (sic) Editions” online Spenser at the University of Oregon looks wonderful. But the citation on the page is “by Risa S. Bear from the John C. Nimmo facsimile (London, 1895) of the British Museum copy of the first edition of 1579.” Okay, is this a typo for 1890? Because I’ve looked at the title page [2] and it says 1890. It’s possible there is an obscure edition of 1895 out there, but the only references for it I see online track back to R. Bear. Websites I absolutely trust, like the Universities of Oxford and Cambridge, reference the 1890 edition only. Okay, it’s probably a typo. What about the text? The site goes into great detail about their transcription methods, and I’m sure they were sincere. But there in January, I see the line, “Led forth his flock, that had been long ypent.” Been, b-e-e-n. Check the black-letter copy. It’s b-e-n-e. Even the most careful of transcribers occasionally see what they think is there, not what actually is, which is why important transcriptions are not done by one person. So that’s two typos, in two paragraphs. Not a great batting average, which is why secondary sources are not as valuable as primary sources. You can also see why every generation removed from the original becomes less trustworthy.

What about music?

Music was obviously far less prevalent in period, simply because so few people (comparatively) read music. Traditional songs tend to appear in lyric centuries before we see them with music. But composed music, even by the prolific “Anon,” was frequently recorded, sometimes with words, where it’s evident the song was meant to be sung, and sometimes as an instrumental piece that was, at some point, associated with a lyric. Let’s go through the same exercise as we did above, and see what a primary period source for music looks like.

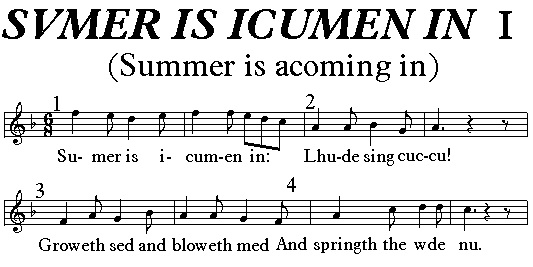

Most people have heard of Sumer Is Icumen In, one of the earliest secular songs in the English language. You can find the words and music all over, some of which looks like this:

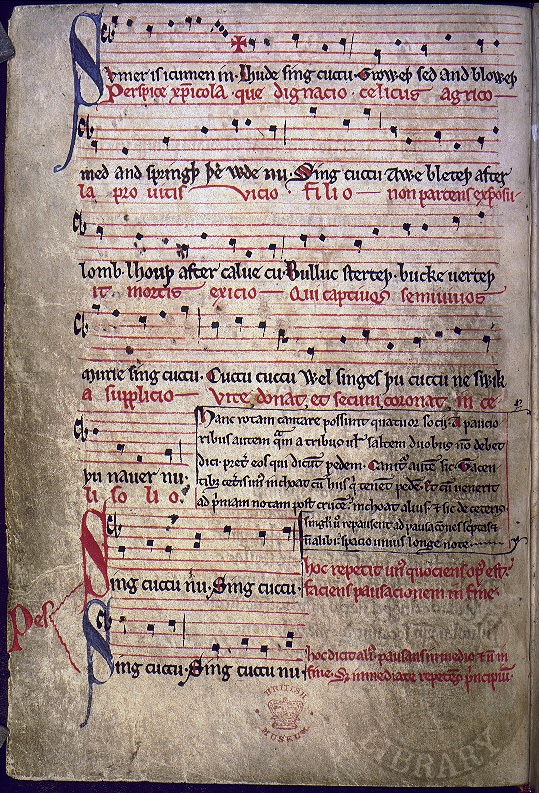

Horribly, you may also see it with the lyric, “Summer is a-coming in, loudly sing cuckoo!” which you should recognize by now is nothing like period. (Why did the modern printer use a V in Svmer but print icumen with a U? Because the manuscript looks that way. We’ll get to that.) This song dates to about 1250, so it is even worse than Shakespeare in the “non-normal” department; the Bard of Avon wrote in Early Modern English (yes, that’s modern), and this is Middle English. You can see you can figure out a lot of it (“groweth” is pretty clear) even with the spelling weirdness, and you can feel secure that this has NOT been corrected to modern language. But what about the music? Does it look normal to you? Then it’s almost certainly NOT period. Here’s the original [8]:

This is actually pretty progressive for 1250, having 5 lines in the staff. That C is a C clef, and the thing that looks like a flat sign, is! The center of the C marks the line that indicates the C note, so the flat is in the B space, indicating Bb is to be sung. (If you read modern music, this is where you say, but C isn’t on a line, it’s on a space! The clefs are completely movable in period music, based on the range of the notes, so trying to sight read period music can make your head explode until you get used to it.) The song begins and ends on F, and an F major scale (Ionian mode) has a Bb in it. There is no time signature, and no measure lines, though if you look carefully, there are faint lines drawn vertically through the staff to indicate the ends of phrases, such as after the first cuccu and after nu. The notes with tails are worth twice, timewise, what the notes without tails are worth. Armed with this information, you can look back at the modern musical notation and see that it is basically correct, though obviously much more structured. Trust but verify! If you think you’re looking for something like this, you’re going to want to use “manuscript” in your search terms.

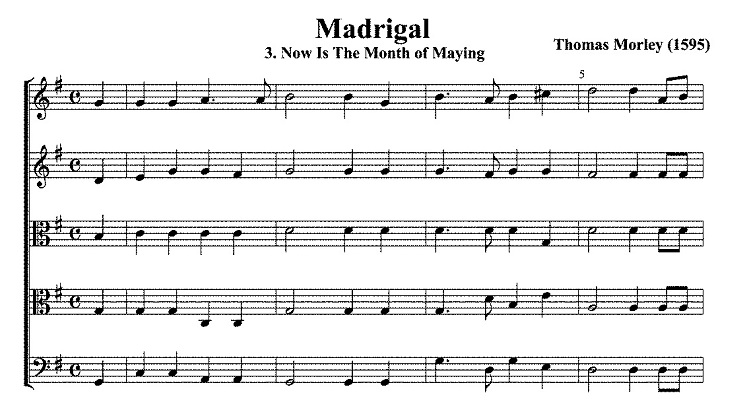

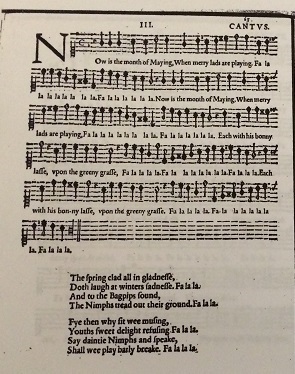

Happily, not all period music will be quite this scary (though some will be more so). You have probably heard Thomas Morley’s “Now is the Month of Maying.” If you put that in Google, you will get very little more information than that Mr. Morley did not think of this piece as a madrigal, but a “ballett”, and it turns out that is all you need. Search “now is the month of maying” “Thomas Morley” “ballett” (it should also work without quotes). The first hit is Wikipedia, the fourth hit is Choral Public Domain Library (cpdl.org), which is generally awesome if you’re just looking to sing. It is filled with stuff that looks like this, which is great to take to a group and sing, but is, as we’ve established, nothing like period because it looks normal. (If you aren’t familiar with a modern C clef, it’s that thing that looks like a capital B. Go figure.)

The third hit in Google is International Music Score Library Project (imslp.org), also known as the Petrucci Music Library [9]. Honestly, the clouds parted and angels sang when I found this site. There is a lot of pre-1600 music. A LOT.

WARNING! Many of the files are modern arrangements and/or transcriptions. Pro Tip: As you learn what period printed music looks like, you should be able to tell it from the modern versions. Many of the files are primary sources; some are hand-written manuscripts. You just have to dig.

So on the “Now is…” page, if you open those files, they all look depressingly modern. A couple of the versions are “faux period” done in Lilypond software, but they are marked as such. Here’s the secret. Go to the bottom of the page where it says “General Information” and under “First publication” it says, “1595 in Balletts to Five Voyces, Book 1 (No.3)”. And it’s a link. Click it. Here it is in all its five-individual-part-book glory. (Be sure you get the 1595 version, which is there in both English and Italian, and not the 1842 Antiquarian reprint. The 1842 version does have the virtue of all the parts being on a single page.)

Yes, you need all the parts individually. Here, the ladder-looking thing is the C clef, so this part, the cantus (melody) starts on G. The C is an indicator of “common time” or 4/4. The Xs throughout are sharps. Beginning and ending the melody in G, we’d expect G major (Ionian mode) to have an F#, but there are also a few accidentals in this piece, so sharps are marked individually. Notice that quarter notes are starting to look like quarter notes, and half notes open in the center, and a whole note an open square. This is early modern musical notation, common throughout the 16th century. The delightful bad spelling is growing less noticeable, just in the 16 years since the printing of the Shepheardes Calender. The more you work with this stuff, the better you will get at recognizing how old something is at a glance.

So now that we have had a look at what a period source looks like, you can make a guess at how little of the music you know is actually pre-1600, at least the way you know it. But unless you are entering Kingdom A&S or some other judged competition with tip-top academic standards, that is not going to be a deal breaker. There are centuries of traditional material that pass for “period-feel” or “peri-oid”, and are much more accessible.

Is it at least “Traditional”?

Welcome to the wonderful world of folk music, full of great songs free from copyright issues and references to the modern world. Even better, because of the fluidity of the folk process, compulsive people have, for centuries, been trying to organize and sort these song-stories. There are dozens of fabulous websites waiting to provide you with all the information you could ever want about traditional songs; unfortunately, they aren’t particularly easy to use, especially if you aren’t sure of the song’s title. Never fear, you can navigate the murky waters with a little vital info.

Child #: Francis James Child (1825-1896) was the grandfather of organizing ballads. Child numbers go from 1 to 305, in no order whatsoever. Radically different songs may be lumped under the same number, and very similar songs have their own number, depending on how well Child liked them. But he was the first, so Child numbers continue to be cited if there is one. All Child-numbered songs can be considered authorless, and some of them are period. Child’s spellings are usually safe, as he preserves even letters we don’t use anymore, like þ and ð.

Laws #: George Malcolm Laws (1919-1994) was an American, and began his system with American ballads and eventually incorporated British ballads. His numbers go from A01 to Z99, and are organized by broad topic; also, letters A through H are reserved for ballads originating in America, so if you find something identified as Laws D14, it’s probably a bad choice for the SCA (As it happens, Laws D14 is “The Schooner Fred Dunbar” and dates back only to 1933, so it’s a VERY bad choice for the SCA.) Many Laws-numbered songs are modern, so it’s better used to rule things out.

Roud #: Steve Roud, a former librarian and current author and editor, organized the Roud Folk Song Index, maintained on the Vaughan Williams Memorial Library website by the English Folk Dance and Song Society. Roud numbers go from 1 until people stop caring. Since EFDSS is all about folk arts, they limit the catalog on their site to pieces truly considered traditional. On the other hand, they have almost 200,000 records on their site, so finding something is difficult, even if you know the Roud #. It’s huge. Roud #19478, published 1765, is “Hey, diddle, diddle (the cow jumped over the moon)”.

For my money, the easiest-to-use folk song index is hosted by Fresno State. Their website is searchable by keywords, so if you’re looking for a song about murder, you can narrow down your choices (well, some… there are a LOT of folk songs about murder). There is a clear field that says “earliest date”. They are volunteers, and are unfortunately sometimes wrong on their dates, but it’s a starting point; if they say it’s a 20th century song, it probably is.

One of the most important sources of old ballads is known as the Bishop Percy Folio, a collection of written and printed ballads, much of which was recovered by Bishop Thomas Percy (1729 – 1811) at the home of his friend, William Pitt (the Elder, 1708 – 1778), where the pages, from a bound volume that had been damaged, were being used as matches to light the fires. Weep with me when you see the *** that represents missing stanzas. Percy made a lot of editorial changes and published everything, but later scholars went back and took out Percy’s bits, so the folio is available in all its glory, with some content that we know goes back to the 12th and 13th c. The book was really expensive. It is now online (see notes). It is virtually unorganized, so you just have to plow through.

Now, time to roll up our sleeves! The best way to demonstrate how to use some of these resources, as well as basic search engines like Google, is to walk through a case study using a song you might know, and want to sing in the SCA.

Case Study #1: Mattie Groves

You may know or have heard Mattie Groves, aka Little Musgrave, aka “Hi ho, hi ho, holiday”, a popular ballad; sex, infidelity, sword fight, murder… what’s not to like? But how old is it? Many of the people singing it are singing a version that dates from the folk era of the 1960s, and while no one will throw stones at you for singing that version, you can do a LOT better if you want to. Start with the obvious: put the title into Google.

The first hit is a YouTube link for Fairport Convention, the modern version. The second hit is a Wikipedia article. NEVER cite Wikipedia in documentation; it is a wiki, a volunteer-written site. Some of the articles are encyclopedia quality, and some aren’t. But there’s no reason to avoid it, because somebody may have done a lot of the heavy lifting for you, plus you can use the time-honored research technique of raiding the bibliography to find sources better regarded in terms of scholarship.

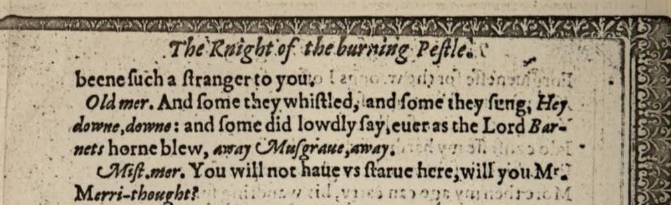

As it happens, the Wikipedia article for Mattie Groves is quite good. It tells you the following important facts: that the song has a Child number, in this case 81, and it is often known by the title “Little Musgrave and Lady Barnard”. If you knew nothing else, you could put “Child 81 Little Musgrave” in Google and the first hit is the Fresno site. It will give you WAY more information than you need, including every version they have found, ever, of this song. Three important take-aways: they give you a Roud number (52), they show you that there are multiple tunes available in Bronson (we’ll talk Bronson in a minute), AND they tell you that a bit of the lyric turns up in the play “The Knight of the Burning Pestle”. A tiny bit of Googling will tell you that KotBP was first performed in 1607 and published in 1613. SCORE! It beggars the imagination that a song being sung by a character in a play in 1607 wasn’t around before 1600, especially when it is an authorless “popular” ballad.

Try another search with some new data, “Roud 52”. The first hit is the Roud site—avoid. The second is a Norfolk (UK)-based folk site which again, tends to have very good information, including a comment by A.L. Lloyd. [A.L. Lloyd was a British singer and ballad collector with a high degree of scholarship, rather like John Jacob Niles in Appalachian America. Both men are well worth paying attention to.] Lloyd comments that “Many people connect the events of this ballad with the district of Barnard Castle, Co. Durham.” (We’ll go back to that later, too, just because it’s fun.)

So how do we get as close as possible to the 1600/1607/1613 words? We need to find out what the section cited in “Knight” looked like, so let’s search “Knight of the Burning Pestle full text”; the first two hits are Project Gutenberg and Archive.org, pick either one. Now use F to search the page, and type in Musgrave. Look!

And some they whistled, and some they sung, (Hey, down, down!)

And some did loudly say,

Ever as the Lord Barnet’s horn blew,

Away, Musgrave, away!

WARNING! Does anything look misspelled? No? Check the detail. Gutenberg is transcribed from a 1913 printing, and Archive from the 1898 printing (they seem to be identical). Pro Tip: When looking for the original version of something, try searching with the title in quotes followed by one or more of the following words: manuscript, quarto, folio, facsimile, black-letter, broadside. These won’t all be applicable to every search, but one of them should get you to something better than a copy of a copy.

Fun fact: When I first taught this class, KotBP was not online in facsimile, but NOW IT IS, and in more than one place. I mean it when I say to keep checking on things you have researched and failed on. The interwebs just get webbier and webbier. A facsimile of the original at the Huntington Library, “LONDON, Printed for Walter Burre, and are to be sold at the signe of the Crane in Paules Church-yard. 1613.” I had previously found two nicely mis-spelled transcriptions, and guess what? They both had errors! So, happy are we that we now have the 1613 version, which appears as follows [10]:

And ſome they whiſtled,

and ſome they ſung,

Hey downe, downe:

and ſome did lowdly ſay,

euer as the Lord Barnets horne blew

away, Muſgraue, away.

Old Merrythought sings bits of several songs in this scene, including Fortune, My Foe, published by John Dowland before 1590, and Sing wee and chaunt it, arranged for five voices by Robert Morley in 1595, so there is little reason to doubt that Little Musgrave was of a similar date.

Now we need the rest of the lyrics, so search for “Child 81, Barnet, downe”. The first hit is Sacred Texts. ST is a VERY mixed bag. Seriously, they have stuff on UFOs. But they also have good webbed translations (and a few originals, like Beowulf) of Arthurian, Celtic, and Norse works. They have occasional errors, but they also have the most complete list of Child’s versions I have found online (unfortunately, without the analysis and background), and because it is in HTML format you can copy, search, etc. But check your fourth hit—that is Child online, courtesy of Google Books. So you can copy and paste version A from Sacred Texts, and learn from Child that it is transcribed from two printed copies, “Wit Restord (sic)” from 1658 and “Wit and Drollery” from 1682. (You can also check Sacred Texts for typos.) So now you know that by the 17th century, it looked like this [4]:

And some of them whistld, and some of them sung,

Hay downe (burden lines are typically only printed in the first verse to save space)

And some these words did say,

And ever when my lord Barnard’s horn blew,

‘Away, Musgrave, away!’

That’s as well as we can do, until someone finds an older copy of the ballad (which does happen periodically). But it beats the heck out of 1965 lyrics, AND we have placed the song in period.

So how much older could it be? Remember Lloyd’s comment about Barnard Castle, Co. Durham? Searching “Barnard Castle Durham” will get you this, among other things: Barnard Castle was built by Bernard de Balliol (d. 1154) starting in 1125, and by his son Bernard II (d. ca. 1190) [5]. If you go down that rabbit hole, more research into the Balliols will tell you that Bernard and his son were both famous campaigners and were away from home a lot. (They probably had lonely wives.) Just west of the Castle lies the village of Great Musgrave, named for the Musgrave family who held manor lands there, around the same time as the Balliols. Was there a love triangle scandal among the great families of Durham in the 12th century, immortalized in song? It would be astonishing if evidence ever surfaced, but isn’t it cool to pull on threads and see where they lead? Of course this is a ridiculous amount of work to put into a pop song. But putting together a kit of armor is a ridiculous amount of work when you could be playing Frisbee. Ridiculous amount of work for fun is what we do.

But there’s no tune!

As we mentioned earlier, the singers of traditional songs were rarely music literate. On the other hand, they were much more free thinking than we are, and you will frequently find lyrics written down with the note, “To anie pleasant tune”[6]. There are a few books of music extant from the 16th century that contain tunes belonging to popular ballads, but most of the tunes we know were collected “from tradition”, meaning some guy went around the firths and fells making notes on what they heard Scottish grannies singing. These were typically gathered in the very late 19th and early 20th centuries, so nowhere near period, but it’s someplace to start. B.H. Bronson (I told you we’d get to him) published a multi-volume companion set to Child’s work, organized by the same number, and he gives multiple tunes for most ballads. Parts of this work can be found online thanks to Google Books, but it’s abridged. Search [“Little Musgrave” Bronson tunes] and you’ll find the hit part way down the page under “The Singing Tradition of Child’s Popular Ballads” [7]. Sometimes you’ll have to choose between a tune that doesn’t seem to go with the format of the lyrics you have chosen. For instance, if you choose to use the oldest version of the Little Musgrave lyrics, you’ll need a tune that accommodates the burden line, or you’ll have to tweak it (and that’s how new tunes start!).

This is also a good place to talk about Traditional Tune Archive. Andrew Kuntz and Valerio Pelliccioni made this site as a repository and study project for traditional fiddle tunes. There is little if any music that is pre-1600, and generally no lyrics, but the music is accessible and copyright-free. If you are looking for a tune to appropriate for your next work, there are hundreds available here.

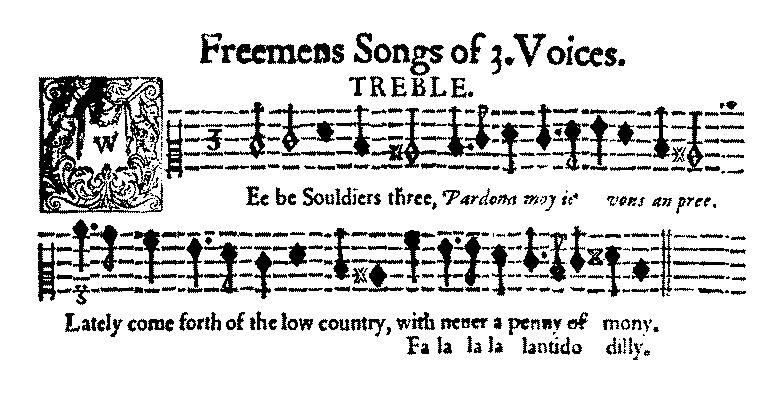

Case Study #2: We Be Soldiers Three

Again, you may or may not have heard this song, but it’s pretty popular. Search “We Be Soldiers Three”, skip over the sites you don’t recognize, and the YouTube hits (okay, stop and watch Owain Phyfe, and grumble that he now sings with the angels for real), and you’ll see Norfolk Folk again, with a big Roud number (8340). Follow this link, and you’ll quickly find out that it was first printed by Thomas Ravenscroft in his work Deuteromelia in 1609, and that the lyrics refer to events unfolding in the Netherlands during the reign of Charles V (1500-1558). Now search “Ravenscroft Deuteromalia” and the first hit is Thomas Ravenscroft Deuteromalia (1609) on the site maintained by Greg Lindahl, and if you follow the link, it will take you to a facsimile of the 1609 printing, or at least the first page. Well, that’s frustrating. (You’ll note “Treble”, which is the melody, as well as the “Tenor” part.)

Here’s our ladder-looking C-clef again, which means this melody starts on D. The 3 is the time signature, ¾, and there are our Xs as sharps. Let’s search again, this time with the magic word: IMSLP. Search IMSLP Ravenscroft Deuteromalia. And there it is, the whole 1609 printing, with the second page, containing the bass part and all the verses.

If you go back to Greg’s Ravenscroft site, and scan through some of the titles, you’ll see “Hey Ho Nobody At Home” and “Three Blind Mice” and they will look SORT OF like you know them, but not exactly, because even after words and music were being printed, they continued to grow and change. That’s why you shouldn’t assume a song that has survived to the present day sounded the same to our pre-1600 forebears. But it should get you interested in what HAS happened to music over those centuries.

Case Study #3: Ce Mois de Mai

Everything we’ve discussed relative to looking for a song is true in other languages. If you are looking with lyrics in modern French (or Spanish, or…) you will NOT find the period version. There are online dictionaries for MANY medieval language forms, though they are obviously more useful if you have some familiarity with the language. You will eventually find that there are certain key words that are your friends; for example, the common French word “quand” (‘when’) was commonly spelled quanT in Middle French, and it turns up in a lot of song titles and lyrics.

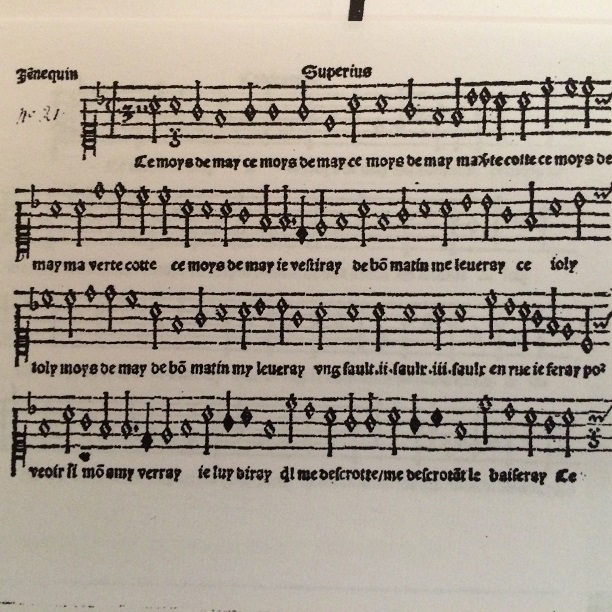

“Ce Mois de Mai” is a jaunty French chanson by Clément Janequin (c. 1485 – 1558). Searching title and author will get you all the normal YouTube hits and modern sheet music, as will searching for the period spelling “Ce Moys de May” (it doesn’t always work, sadly). Why are you wasting my time? I hear you cry. Let’s go to IMSLP! Yes, there it is. In modern notation, just as “Now is the Month of Maying” was. Going to General Information… no link. Here, the gold is in “Misc. Comments” where we find “In Trente et une Chansons Musicales – Pierre Attaingnant, Paris, 1529.” Pierre Attaingnant was a musician, but also a printer, and he printed LOTS of songs he didn’t write. Go up to the IMSLP search window and type Trente et une Chansons Musicales Pierre Attaingnant. Poof! There it is.

Some things of note: we have “Superius” which, like “Cantus”, indicates the melody. We have our ladder C clef, and here the C with a line through indicates “cut time”, or a half-note base. The 3 tells us that the time signature here is 3/2, hence all the half and whole notes. We’re in the key of F Major, and there is the flat we expect on the B line. Other cool things: the S-squiggle under “moys” and at the end is a segno, telling you to return to the top. Oddly, there’s no fine, so you have to know where to stop (at “vestiray”). Also, one of my favorite things, the little squiggle in the end of each line is in the place of the first note on the next line, so you have a clue where you’re going. (Why did we stop doing this?)

Pro Tip: IMSLP often lists collections under the publisher, so the period version might be filed under another name. You are unlikely to find period music under the title of the individual piece unless it was published that way, which is really typical only for much longer musical compositions. That’s why you want to look for Deuteromalia and not “We(e) Be Soldiers Three”. Always search all the information blocks, because the answer is usually there.

Case Study #4: Henry V, Prologue

So many people take Shakespeare as a “given” for being period, which is silly, because a chunk of his plays are not known to have been performed until after 1600, and the ones that we know existed in 1600 did not necessarily exist in the form we know. Shakespeare kept tweaking the plays throughout his lifetime, and somebody, possibly several somebodies, went right on tweaking until at least the great Folio of 1623, published several years after Shakespeare’s death in 1616. Again, no one will throw stones at you reciting Shakespeare, but before you get caught with your pants down, it’s worth doing some looking.

Say you have decided to do the prologue from Henry V, “Oh, for a Muse of Fire…,” or in the original spelling, “O, For a Muse of Fire, that would ascend/The brightest Heauen of Inuention.” Great speech. Search “Henry V prologue first folio” and up will pop the University of Victoria copy from the First Folio. Ta-da! But wait, while you’re there, click on the “Edition: Henry V” above the large title line, and it will take you to the page that lists all the resources for this work. Scroll down, and you’ll see they also have the Quarto edition of 1600. Score! Click on that. Read it from the beginning. Your speech is not there. The Quarto edition begins with Exeter asking the King if he should call in the Ambassadors, which is Act I, scene 2 in the 1623 Folio edition. Not only is the Prologue, strictly speaking, not period, we can’t even be sure that Shakespeare wrote it, because the version of the play published while Shakespeare was still alive does not contain it. It sounds like him, it probably was him, but we truly cannot be sure, and scholars have been wailing about it for centuries. If you are a fan of doing Shakespeare, the Wikipedia article “Chronology of Shakespeare’s plays” is actually excellent and will give you a starting point in your research.

Case Study #5: The First Sestina (and troubadours in general)

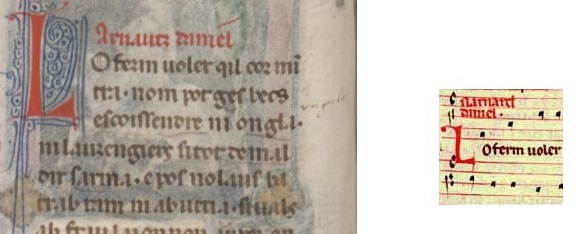

A friend posted onto Facebook one day in the SCA Bards discussion group, “It says everywhere that Arnaut Daniel, a 12th c. troubadour, wrote the first sestina. How long will I have to look to find out what it really looked like in period?” The answer (for me) was about 15 minutes. If you are into the poetry and songs of the troubadours, you have the enormous benefit of a couple of really obsessed people. If you go to the Wikipedia article on Arnaut Daniel, and scroll all the way to the bottom, under “external links” you will find a link that says “Arnaut Daniel: Complete Works (in English and Provençal)” which will take you to trobar.org, the website of Leonardo Malcovati. Leonardo has links to individual pages for pretty much every known work by an Occitan troubadour, in English and the original Occitan/ Provençal, which was the language of the south of France in period. Sadly, he doesn’t have a complete list of extant manuscripts where each work is to be found, so man’s search for knowledge must continue. You can use the Occitan text to search for manuscripts, using the first line, “Lo ferm voler” and remembering to make that V a U, so “Lo ferm uoler,” or you can go to the Wikipedia page for “Troubadour” and scroll to the bottom for the list of chansonniers (French for ‘songbook’). Again, there is no list of songs, and the shelf marks are not live links, but enter another obsessed person.

Courtney Wells’ website (https://trobaretz.wordpress.com/) has live links to the specific document, or sad notes that the document is only available by subscription. By happy accident, the thumbnail photo for Chansonnier manuscript G happens to BE “Lo ferm voler”, but when we go to Courtney’s site, we find that manuscript G is in Milan behind a subscription wall. Happily, the works of the troubadours were much studied, and many of the manuscripts duplicate a number of works. A little searching reveals that Lo ferm voler is also in manuscript M, happily available from the Bibliothèque Nationale. There is more than one way to skin a Milanese cheapskate.

The larger photo is M; the thumbnail is G, which has the music, added about a century after Daniel wrote the lyric. The full music line is visible on one of the many YouTube videos of the piece, or at Troubadour Melodies Database (see notes).

Case Study #6: Ja Nus Hons Pris

Now we’re getting hardcore. This is an oft-recorded song, which you can absolutely learn off a CD, but “I learned it off a CD” does not look good in your documentation. Plus, if I have infected you with my disease, you should be asking, but how do I know I really did a period-correct version?

You can do the same things we’ve already done, but I’m going to give you a new magic word. We’re looking for a song in French. Remember what a songbook is called in French? Search ja nus hons pris chansonnier; your first hit is a paper at Academia.edu called “Richard Coeur de Lion and the Troubadours” by Xenia Sandstrom. Not only it is full of good info, she has the song, a complete translation, and BOTH the extant manuscript chansonniers dating from the 13th c. Thanks, X, triple Yahtzee. Pro tip: This works for many languages; Spanish cancionero, Italian canzionere, Latin/sacred antiphonary or antiphonal. Learning the period words for ‘songbook’ really helps your searches. You will get collections of poetry also, because lyric=song for most of our period.

The good Xenia has images of two extant manuscripts, but even if she had only given you the shelf tag, it would be easy to find. Learn to recognize and LOVE Manuscript markers. Here the first is Bibliothèque de l’Arsenal, Ms-5198 réserve. Put that in Google; the first hit is the document and all the data. The second she gives as Français 846, with the note “Ja nus hons pris found on folio 62v – 63r. (digital pages 154-155)”. If you ONLY put Français 846 in Google, DIAMM is your first hit, and you can get there from there. DIAMM (the Digital Image Archive of Medieval Music) is a searchable way to get to a lot of European manuscripts. You’ll need an account, but it’s free (though they’ll be happy to take your money). But the fourth link, a scary-looking string of numbers, says it’s from gallica. Gallica is the digital project of the BNF, the Bibliothèque nationale de France. If you are looking for a French manuscript, and it’s in France, and it’s online, it’s going to be at Gallica. Manuscripts are generally filed by folio, or sheet, and the two sides are called recto ‘the right side’ and verso ‘the other side’, so a song on two pages is frequently listed as here, the back side of sheet 62 and the right side of sheet 63, which to us is page 124 and 125 plus any introductory material.

Looking at the two copies, you’ll see that the second, the chansonnier Cangé, has the melody that most people sing, and the other, the chansonnier de Navarre… doesn’t. (There are a few lyrical differences, and different scribal abbreviations as well.) Is one wrong? We’ll never know. It is enough to know that melodies were tinkered with just like words, and unless you have the notation in the author’s hand, it’s almost impossible to know what they intended. At least both are demonstrably 13th c. tunes.

As you work more with manuscripts you’ll learn to recognize shelf marks. The Selden Carol Book, which includes the Agincourt Carol, is MS. Arch. Selden. B. 26 at the Bodleian Library at Oxford University. MS. is ‘manuscript’, Arch. Selden. is ‘Archivum Seldenianum (Selden’s archives)’ and B. 26 is just a filing number. Happily, you don’t have to know any of that; just put MS. Arch. Selden. B. 26 in Google and you’ll get where you need to go. But the more you pay attention to what shelf marks look like, the more easily you’ll be able to spot them in annoyingly dense margin data. Soon you’ll recognize different collections, and you won’t go looking at Gallica for something at Oxford. And when or if you include images in your documentation or in posts PLEASE be part of the solution and not the problem. Too many people post cool stuff on Pinterest with no provenance (a fancy word for ‘where it came from’), which means anybody who cares to learn more has to start at the top of the rabbit hole and work down. Be kind; TAG. Also, be sure to GO to the manuscript and don’t just cite the shelf mark. It may turn out that the manuscript is, say, lute tablature, and if you talk about notes as though you saw notes, it will be obvious that you stopped documenting a little early.

I’ve been at this for years, and my Google-fu is strong. Nothing will replace simply looking and looking and digging through what you find. It will get easier, and fabulous stuff is being webbed every day that might be the link you’re looking for. It’s a great time to be a researcher.

Adelaide’s Google-fu Tips:

1. It’s there, somewhere, or it will be soon. Keep looking.

2. Everybody is a worse scholar than you, and cited something without checking it. CHECK IT.

3. Remember your quotes and minus signs while searching, to cut down on false hits. If you don’t know what that means, or you don’t know about Google operators in general, I HIGHLY recommend this article: https://www.searchenginejournal.com/google-search-operators-commands/215331/ The “around” command will change your life.

4. There is more to find. Cool always leads to cooler.

Notes

[1] The Globe Edition. Complete Works of Edmund Spenser Edited from the Original Editions and Manuscripts by R. Morris … With a Memoir by J. W. Hales, London: MacMillan & Co., 1869.

https://books.google.com/books?id=BTNYAAAAcAAJ&pg=PA446&lpg=PA446&dq=A+Shepeheards+boye+%28no+better+doe+him+call%29&source=bl&ots=VQ95MyY14A&sig=67RPVT5bvu_r-qc1gTMSo3bKteo&hl=en&sa=X&ei=9KxwVbrzEYvutQWmooGQDg&ved=0CDYQ6AEwBA#v=onepage&q=A%20Shepeheards%20boye%20(no%20better%20doe%20him%20call)&f=false

[2] Spenser, Edmund, The Shepheardes Calender; the original edition of 1579 in photographic facsimile with an introduction by H. Oskar Sommer, London: John C. Nimmo, 1890.

https://archive.org/stream/cu31924013125392#page/n51

[3] Renascense Editions, various editors, WWW: University of Oregon, 1992-2008. https://pages.uoregon.edu/rbear/shepheard.html

[4] Child, Francis James, ed., The English and Scottish Popular Ballads, Boston: Houghton, Mifflin & Co., 1882–1898.

[5] “Barnard Castle”. SINE Project, WWW: University of Newcastle upon Tyne, 2002-2004.

https://www.sine.newcastle.ac.uk/view_structure_information.asp?struct_id=21

[6] Rollins, Hyder, ed., A Handful of Pleasant Delights (1584) by Clement Robinson and Divers Others, Dover, 1965, (A reprint, the original was published in 1924.), p. 52.

https://archive.org/details/handfulofpleasan00robiuoft

[7] Bronson, Bertrand Harris. The Singing Tradition of Child’s Popular Ballads, paperback, Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1976.

[8] “Sumer is icumen in” in Wessex Parallel WebTexts, ed. Bella Millett, WWW: English, School of Humanities, University of Southampton, 2003.

https://www.soton.ac.uk/~wpwt/harl978/sumer.htm

[9] IMSLP Petrucci Music Library (International Music Score Library Project). They are a subscription site, but you can still download anything you want as a non-member. You’ll just have to put up with a lot of pop-ups saying, “Are you SURE you don’t want to give us money? We’d like your money.” The annual membership is around $26 (yeah, per YEAR), so it is very worth being a member. These people are awesome and deserve our support.

https://imslp.org/

[10] Beaumont, Francis and John Fletcher, The Knight of the Burning Pestle, 1613 printing. Also found at the Folger Shakespeare Library.

https://books.google.com/books?id=2d49AAAAIAAJ&printsec=frontcover&source=gbs_ge_summary_r&cad=0#v=onepage&q&f=false

Books Online I paid a lot for:

Chappell, William, Old English Popular Music, New York, 1961 [originally published 1838]. Melodies and lyrics to early popular songs in modern notation.

https://archive.org/details/oldenglishpopula02chapuoft

Percy, Thomas, Frederick James Furnivall, John Wesley Hales, Bishop Percy’s Folio Manuscript: Ballads and Romances, London: N. Trübner, 1868.

https://archive.org/stream/bishoppercysfol00halegoog#page/n8/mode/2up

Websites You Might Like:

Internet Archive. This is a gold mine, but it’s also kind of like the warehouse where Indiana Jones stashed the Ark of the Covenant. It’s best to use your search engines until you identify a work, then look here. There are complete period and near-period books of music here.

https://archive.org/

British Library Digitised Manuscripts. Again, too much to plow through, but you’ll find a wealth of period texts, music, etc.

https://www.bl.uk/manuscripts/

Bibliothèque nationale de France. Froissart’s Chronicles, Christine de Pizan, etc. The English-language version is fairly functional, so don’t be scared off just because you have no French.

https://www.bnf.fr/en/tools/a.welcome_to_the_bnf.html

Cantigas de Santa Maria. I didn’t bother doing a case study on the Cantigas, because everything you want is usually here: sheet music, lyrics, pronunciation guide, manuscript links.

https://www.cantigasdesantamaria.com/

DIAMM (the Digital Image Archive of Medieval Music).

https://www.diamm.ac.uk/

Folger Shakespeare Library. I sometimes have problems here asking to sign in, but if you around the corner to the LUNA Digital Image Collection, you should be able to browse freely.

https://luna.folger.edu/luna/servlet

Medieval Music & Arts Foundation. A little hard to navigate, but again, they have saved you huge amounts of time if you do some looking. Hit the Early Music FAQ page, and you’ll find things like a discography link for Guillaume Dufay, which has enough info (often including manuscript numbers!) to help you not only find a CD you might love, but the documentation to go with it.

https://www.medieval.org/

https://www.medieval.org/emfaq/composers/dufay.html

Medieval Primary Sources, Seminar X: Poetry and Song. This is from the U of Lancaster, and has incredible links and bibliography. Some things are annoyingly behind a ULanc wall, but if you go to, say, the discussion of the Agincourt carol, the links will take you right to the two extant manuscripts.

https://www.lancaster.ac.uk/staff/haywardp/hist424/seminars/10.htm

Monastic Manuscript Project. If you are looking particularly for sacred music, this site is an amazing shortcut to places that have medieval manuscripts available online. It doesn’t have a lot of detail for what you’ll find, and the links are often broken as places go behind pay walls, but on one of those days when you have time to go down a rabbit hole, it’s a treasure trove.

https://www.earlymedievalmonasticism.org/listoflinks.html#Digital

The Music of Thomas Ravenscroft. Presented by Greg Lindahl, there are facsimiles of much of Ravenscroft’s works, plus links to other interesting sites.

https://www.pbm.com/~lindahl/ravenscroft/

Outlaws and Highwaymen. The author (Gillian Spraggs) of a book by the same name has a great deal of her research material here, including original (un-spell-corrected!) text from the 1556 English translation of Thomas More’s Utopia. Also, not surprisingly, you’ll find good info for documenting outlaws and highwaymen, a favorite topic for SCA bards.

https://www.outlawsandhighwaymen.com/

Rhyme Zone. An online rhyming dictionary and thesaurus (any poet who says they don’t use a rhyming dictionary either lies or writes bad poetry). Best of all, there’s that search engine to the complete works of Shakespeare, allowing you to check for period word usage.

www.rhymezone.com

Sacred Texts Online. Okay, I know they have stuff on UFOs. But they also have good webbed translations (and a few originals, like Beowulf) of Arthurian, Celtic, and Norse works as well as studies thereon. Tiptoe through the trash and look for the treasure.

https://www.sacred-texts.com/

Traditional Tune Archive by Andrew Kuntz & Valerio Pelliccioni. LOTS of music, generally copyright-free under Creative Commons, but not much pre-1600. Mostly geared to fiddle tunes.

https://tunearch.org/wiki/TTA

Trobar, the website of Leonardo Malcovati. Much of the site is devoted to prosody and various fixed forms of poetry; if you’re looking for troubadour songs, just stick to that page. The rest is fascinating if you’re a poetry geek.

https://www.trobar.org/troubadours/

Troubadour Melodies Database. Katie Chapman did this work for her dissertation, and figured, why not share? It’s still in beta, so the look changes, and it can be scary if you aren’t a musicologist.

https://www.troubadourmelodies.org/

Trobaretz, the website of Courtney Wells, who has done a lot of your work for you in finding links to manuscripts so you don’t get lost at BNF or fall down too many rabbit holes.

https://trobaretz.wordpress.com/

The University of Cork has a collection of medieval Irish works in original and translation, called CELT: the Corpus of Electronic Texts. If you’re writing anything modeled on an Irish example, you have to know about this site:

https://www.ucc.ie/celt/

The University of Michigan’s “Corpus of Middle English Prose and Verse” features un-edited versions of Malory’s Le Morte d’Arthur, Piers Plowman, Chaucer, and other gems.

https://www.hti.umich.edu/c/cme/

The University of Toronto has a number of useful things from its library webbed. Among other treasures is the original 1609 printing of Shakespeare’s sonnets.

https://www.library.utoronto.ca/utel/ret/shakespeare/1609.html

The University of Victoria also has Shakespeare online, along with interesting discussion about the concepts of drama, tragedy, and comedy in the medieval world. Go to “the Theater”.

https://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/index.html

The Traditional Ballad Index, hosted at Fresno State University, mentioned above.

https://www.csufresno.edu/folklore/BalladIndexTOC.html

You can find more of my articles on bardic and other arts at the Raven Boy Music website. https://www.ravenboymusic.com/articles/