A Little History

Happily, this state of affairs did not last long. Musicians teaching church music used cheironomy, or hand signals, to indicate tonal changes, and sometime around 800 CE, the flowering of church music in the

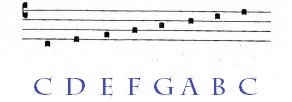

Enter Guido d’Arezzo, 10th century music theorist, who had the fabulous idea to put the neume marks on lines and indicate how the lines corresponded to notes [5, 6]. Guido designed a four-line staff to keep notes in absolute relation to each other, and two key signatures which could be placed anywhere on the staff as needed to indicate what note corresponded to each line and space. Here is the C clef on the top line, and the corresponding note values:

Since Guido was setting music mostly for men’s voices, using a C clef would often result in notes off the staff (which nobody likes), so he also used an F clef notation:

Now the problem was how to teach a student where, say, F was in relation to C, such that written music would get the right notes out of the singer. Thus was born “solmization” or “solfege”.

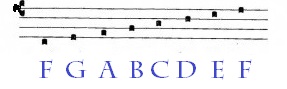

The hymn was written by Paulus Diaconus (ca. 720-799), best known for his work Historia Langobardorum, the History of the Lombards. That’s Guido. Isn’t he cute?

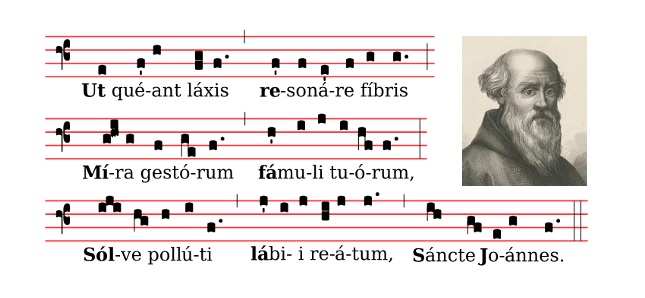

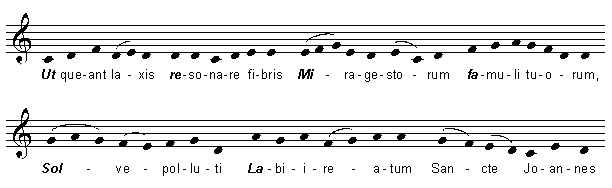

The same notes are given in modern notation below. You can see how movable clefs allowed the notes to appear happily in the middle of the staff, even with only four lines, where modern notation has the notes dragging off the bottom of the staff.

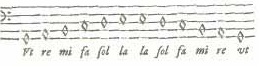

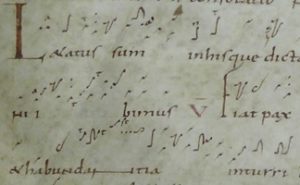

St. John Hymn, “Ut queant laxis” ca. 800 CE

(Before you ask, it means “That these your servants may with all their voice, sing your marvelous exploits, clean the guilt from our stained lips, Saint John”.)

Now look at the syllables that begin each musical phrase: Ut – Re – Mi – Fa – Sol – La. Ut falls on C, Re on D, Mi on E, Fa on F, Sol on G, and La on A. By combining these syllables with the Greek names of the letter-notes (i.e., alpha, beta, gamma), a mode could be expressed. For Guido, the lowest note he wanted to express was ut on G, or gamma, so “gam ut” was the starting point; eventually the term “gamut” came to mean the entire scale [7]. As late as 1597 in England, solfege was limited to six notes, usually expressed starting on gam ut (the clef here is an F clef) [8]:

The syllables remained ut-re-mi-fa-sol-la until 1673 when Giovanni Bononcini first published them as do-re-mi [9, 10]. The seventh was argued over for centuries, and was alternately published as “sa” (for the first syllable in “Sancte Joannes”), “si” (changing the J in Joannes for a Latinesque I for Sancte Ioannes), and “ti” (so there aren’t two notes that begin with “s”). Italy and France still tend to use si, while English-speakers (and fans of “The Sound of Music”) tend to use ti, which dates only to 1845 [11, 12].

Modern-looking Music, and Getting From Blob to Blob

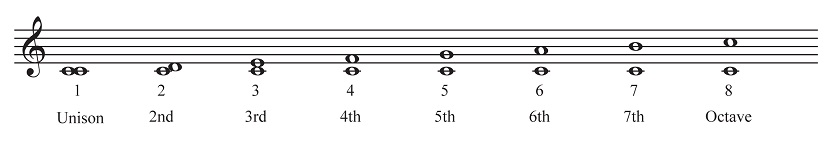

Once we locked ourselves into the standard Every Good Boy Does Fine upper staff and the Good Boys Do Fine Always lower staff, we no longer had to wonder what note was expressed on which line. (If you’ve never considered it before, the round tummy loop of the treble clef circles the G line and the little eyes of the bass clef straddle the F line. They are still telling you what note goes where, but since they never move, we mostly ignore them.) Modern music theory goes back to math (the Greeks would be so happy) and expresses notes in strict mathematical relation to one another, rather than using the solfege syllables. Sight singing from modern music is all about the numbers, specifically, distance in staff positions, which can be expressed like this:

In modern musical notation, these blobs are always going to represent the same notes, but keep in mind that in medieval and renaissance notation, the clef was still entirely moveable. It is therefore more important to understand what the space between the blobs represents, rather than learning fixed notes. Here, for example, the 4th is shown as a C and an F, but it’s better to learn it as four staff positions (here from line, past space, past line, to space). If you start at A and move space-line-space-line up to D, you also have a 4th. Any note four staff positions from the note before it makes a 4th. (It becomes tougher in some other keys, because there may be sharps and flats involved to correct the number of semitones, but we’ll get to that in a minute.) So if you don’t know where specific notes fall on the staff, rejoice! You can still sight sing by learning the relationships, and you will be ahead of modern sight singers when you move to neume or other non-modern notation.

Let’s go through the relationships one at a time (or maybe two) …

Unison: Obviously, when the following note is on the same line (or space) as the previous note, it’s going to be the same note. A boon to the lazy sight-reader!

2nd: The second occupies the adjacent position on the staff. If the first note, as C here, is on a line, the second will be in the adjacent space, and vice versa. The trouble is, depending on WHICH notes are adjacent, the interval for the second will not always be the same. Some seconds are major seconds and some are minor seconds. Why? Blame those crazy Greeks and their favorite mathematical ratios, whose relationships aren’t linear:

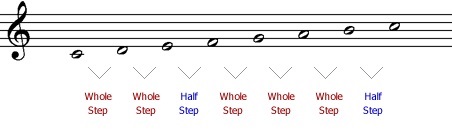

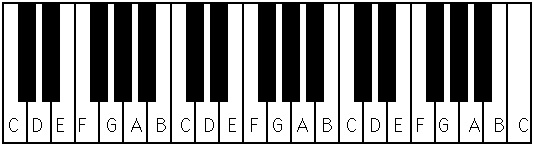

Every octave is divided into “steps” based on the mathematical ratios between the notes. Because of the way the math works out, five of the steps are larger, and we call them “whole” (or “tones”), while two are smaller, and we call them “half” (or “semitones”). The half-steps fall between E and F and between B and C. This is really easy to see on the piano:

There are no black keys between E and F and between B and C. There isn’t room, because they are only half-steps. (It is also a half-step from a white key to a black key and vice versa, e.g., from F to F#.) Moving from C to D is a whole-step (there is a black key between them), and so is D to E. This interval is a major second. Moving from E to F, however, is a half-step; this interval is a minor second. There is nothing on the staff to tell you the difference, you just have to learn where the half-steps fall (if it were easy, everybody would do it!).

You may observe that if the song is happy-sounding, there are fewer minor intervals, while songs of death, doom and gloom seem to feature more minor intervals. This tends to happen not because there are more minor intervals in the octave (never—there are always two natural half-steps, at least in Western music), but because of where the half-steps fall in the octave. (This is all about modes, but we’re not going there today.) We may (sadly) refer to a key as minor, but it is the same length as a major key. When we talk about intervals, though, major and minor have nothing to do with sound mood—the terms are all about actual distance. A minor (i.e. smaller) second is a half-step; a major (i.e. bigger) second is a whole-step. You’ll see later that a minor third is a half-step plus a whole-step, while a major third is two whole-steps. The minor is always the smaller of the two.

So what does a second sound like? Minor second, adjacent staff position, one semitone (half-step); this is si-DO. The opening to the Jazz standard “What’s New?” (How is the world treating you?) is si-do, as is “I’m dreaming” from “White Christmas” (actually si-DO-si). Major second, adjacent staff position, two semitones (two half-steps or one whole-step); this is do-re. “Doe, a deer” is do-re-mi; “Frère Jacques” is do-re-mi-do and “Row, Row, Row Your Boat” is do-do-do-re-mi.

3rd: A third will be line-to-line (as above, C to E) or space-to-space. Once again, depending on whether you involve a half-step (or semitone), you’re going to have major and minor versions. Minor third, three staff positions and three semitones (half-step plus whole-step), la-DO: “To dream (the Impossible Dream)” is la-DO. It is also mi-sol; “Mi, a name I call myself” is mi-fa-sol-mi-sol-mi-sol. Major third, three staff positions and four semitones (two whole-steps), do-mi: “A female deer” is do-mi-do-mi; “Oh, when” of “When the Saints Go Marchin’ In” is do-mi (full line is do-mi-fa-sol).

4th: Yea! There is NO WAY to get four staff positions away without throwing in a semitone, so we call the fourth “perfect” because there is no major/minor nonsense. Perfect fourth, four staff positions and five semitones (two whole-steps plus a half), do-fa: “Here Comes the Bride” is do-fa-fa-fa. “Look Down” from Les Miz is do-fa, as is “Tonight” from West Side Story (and a host of other show tunes’ opening lines).

For completeness’ sake, I’ll mention the so-called Tritone, which is three adjacent whole steps. Unless you’re singing in Lydian mode, you probably won’t need it, but it is fa-si, or “Maria” from West Side Story (actually fa-si-DO). You’ll also hear this interval in the theme from The Simpsons.

5th: The fifth, like the fourth, is perfect. Perfect fifth, five staff positions and seven semitones, do-sol: “Twinkle, Twinkle” (and “The Alphabet Song”) is do-do-sol-sol; the Star Wars theme is do-sol. (Okay, do-sol, la-mi-re-DO-sol, thus Star Wars teaches you both do-sol ascending and DO-sol descending.)

6th: Sigh, we have left perfection behind us, and once again have a major and minor. Minor sixth, six staff positions and eight semitones, mi-DO: “The Entertainer (The Sting)” is re-re#-mi-DO-mi-DO-mi-DO. (There’s a better way to represent “re#” but it’s a bit beyond our scope for now.) Also “every mother’s child” from “The Christmas Song” is re#-mi-DO-si-DO. Major sixth, six staff positions and nine semitones, do-la: “My Bonny Lies Over the Ocean” is the definitive do-la example. (People who have never heard anything but the first line of the song still know this interval from that song.)

7th: There are two of these, alas. Minor seventh, seven staff positions and ten semitones, re-DO: Star Trek! Also “There’s a (place for us)” of “Somewhere” from West Side Story. Major seventh, seven staff positions and eleven semitones, do-si: It’s that weird note in the Superman theme; also “Bali Hai” from South Pacific is do-DO-si, so if you can mentally skip the octave, you can find the ascending seventh. (Scarily enough, this is also the beginning of the Doctor Who theme, as well as the wail from “The Immigrant Song.”)

Octave, which brings us back to DO! If you have trouble finding a full octave jump, think “Somewhere (over the Rainbow…)” or “Chestnuts (Roasting on an Open Fire…).”

Whoo-hoo! We’re done! Oh, wait… you’ve learned how to go UP to all the notes in the octave (the ASCENDING intervals) but not how to go DOWN to them. So here are some mnemonics for the DESCENDING intervals:

Minor second, DO-si. See ascending examples for minor second and major seventh.

Major second, re-do: “Heaven (I’m in Heaven…)” from “Cheek to Cheek.”

Minor third, DO-la: “Hey, Jude.”

Major third, mi-do: The Jac-ques part of “Frère Jacques.”

Perfect fourth, fa-do and DO-sol: “Born Free.” Also see ascending perfect fifth.

Perfect fifth, sol-do and DO-fa: “Feelings.”

Minor sixth, DO-mi: “Love Story,” “Where do (I begin…)”.

Major sixth, la-do: “Moonlight (Becomes You)” and “Sweet Ca(roline).”

Minor seventh, DO-re and Major seventh, si-do: Honest, I looked and I thought, and I could not come up with descending seventh examples that weren’t obscure Jazz pieces, which will tell you how little you’re likely to need to know them.

And that’s it! All you need is practice! Yes, I know, it is SO much easier to learn intervals by hearing them, but sometimes it just isn’t possible. If you can muddle your way through a few easy songs, you’ll be surprised at how quickly the distance between notes starts to mean something in your head. You have a lifetime of music-listening on which to draw, so you might as well start using it!

Adelaide de Beaumont (mka Lisa Theriot)

lisatheriot@ravenboymusic.com

Facebook: Lisa Theriot

References

[1] Randel, Don Michael, ed., The Harvard Dictionary of Music, Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2003, “Pythagorean scale,” pg. 696. After tinkering by a number of notable Greeks, the scale was set with relative permanence by Euclid (in his Sectio canonis (Division of the Canon) and brought to the medieval world in Boethius’ De musica, (early 6th c.).

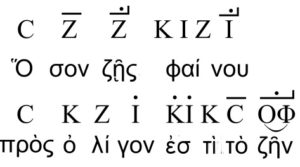

[2] ibid., “Seikilos Epitaph,” pg. 767. The notation looks like this (the lyrics are in Greek, the Arabic letters represent note values, and the line/dot row shows timing):

[3] Isadore of Seville, Etymologies, Book III, section 15, “De Musica et eius nomine,” (Of music and of its name). He writes, “Nisi enim ab homine memoria teneantur soni, pereunt, quia scribi non possunt.” It always sounds smarter in Latin.

[4] Laon, Bibliothèque municipale, ms. 239. Graduel dated circa 900.

[5] Guido d’Arezzo, Micrologus, written ca. 1025-1028.

[6] Grove, George, Sir, Dictionary of Music and Musicians, Volume 1, pg. 369 (s.v. clavichord). London, England. UNT Digital Library. https://digital.library.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metadc31504/ Guido actually called all the lines “claves” or keys (‘clef’ is French for ‘key’), and C and F were “claves signatae” or “sign keys”.

[7] ibid, s.v. gamut, vol. I, pg.580.

[8] Morley, Thomas, A Plaine and Easie Introduction to Practicall Musicke, London : Peter Short dwelling on Breedstreet hill at the signe of the Starre, 1597. https://www.reading.ac.uk/web/FILES/special-collections/featuremorley.pdf

[9] Bononcini, Giovanni Maria, Il Musico prattico, published 1673 in Bologna.

[10] Grove, s.v. do, vol I, pg. 451. Grove says, “It is said by [music theorist François-Joseph Fétis (1784-1871)] Fétis to have been the invention of G.B. Doni, a learned Della Cruscan and writer on the music of the ancients, who died in 1669. It is mentioned in the “Musico pratico” of Bononcini (1673) where it is said to be employed ‘per essere piu resonante’ (for to be more resonant).

[11] ibid, s.v. si, vol III, pg. 490.

[12] Glover, Sarah Ann, A Manual of the Norwich Sol-fa System: For Teaching Singing in Schools and Classes, Or, a Scheme for Rendering Psalmody Congregational. Norwich: Jarrold & Sons, 1845. Glover is recognized for the use of “ti” so that a single letter could represent the solfege syllables: D-R-M-F-S-L-T.