I present a pair of poems modeled on a pair from the early 15th century.

Background

The anonymous macaronic poems “De Amico ad Amicam” (‘From Lover to Beloved’) and “Responcio” appear in several very different manuscripts. The most widely printed version of the work comes from the Cambridge Library collection [1]. The Cambridge manuscript is a collection of writings, including a well-known version of many of the Canterbury Tales. Works by John Gower also appear, as well as anonymous pieces like “De Amico.” (I have not found any scholar who believes that Chaucer penned the poems; they would be better crafted if he had!) Another copy was discovered in a collection of family papers in Warwickshire, among legal letters and documents concerning a family property dispute [2, 3].

The Cambridge copy was carefully taken down by a professional scribe, clearly with the intent of preservation [4]. The Warwickshire, or “Armburgh” (the family name) copy was roughly written out, presumably because a family member found the work a curiosity and wanted a copy [2]. I completely understand, as I have been fascinated by the work since I read an abridged version in a college text. I copied it out and kept it for years until the internet made further research possible.

The term “macaronic” comes from the work Macaronea (or Carmen Macaronicum de Patavinisis ‘macaronic song from Padua’) by the Italian poet known as “Tifi” Odasi (ca. 1450 – 1492). Published around 1488, the work is a mixture of Latin and vernacular Italian [3]. It is unusual that the eponymous work of a genre is not the first of its kind, but indeed, written works mixing Latin and one or more commonly spoken languages had been appearing for centuries before Odasi’s work. The Carmina Burana (ca. 1230), which mixes Latin with vernacular German and French of its time, is a famous example [5]. “De Amico” and “Responcio” are tri-lingual, alternating lines of late Middle French, late Middle English, and Latin.

The original poems are love poems. Though they were very clearly meant as a conversation, one lover speaking and then the other answering, there isn’t much actual exchange to interest the reader. One could paraphrase them as “I love you” and “I love you, too” and not be far from accurate. From the time I found out there were two poems (“De Amico” is frequently printed without the response), I grieved that there wasn’t more tension in the conversation to draw me into the relationship. Happily, there was a contemporary work on which I could draw for greater drama.

The oldest known version of the ballad designated #1 by ballad scholar and collector Francis James Child (1825 – 1896, for whom the “Child ballad” numbering system is named), which Child called “Riddles Wisely Expounded,” also dates from around 1430. It appears as “Inter Diabolus et Virgo” (‘Between the devil and a maid’) in the Rawlinson manuscript at the Bodleian library [6, 7]. Here, the devil asks riddles of a maiden; if she cannot answer correctly, she must be his bride in Hell. Now there’s a compelling conversation!

The section of the manuscript which contains the ballad also contains a number of proverbs, as well as conventional phrases accompanied by Latin translations. The work is a school notebook from Exeter, which shows how Latin was being taught to young men of the early 15th century [8]. “De Amico” was probably written by just such a schoolboy, albeit grown. The poem shows clearly that English was his native tongue; the facility of language is much greater in the English lines than the French, which are very formal and stylized, and the Latin, which shows a marked inattention to case. I believe that the subject matter from the Rawlinson manuscript and the form of the Cambridge manuscript make for an intriguing yet suitable combination. All source poems are attached as Appendix 2.

Methods and Techniques

Based on currently known work, this piece’s meter and structure are unique [3]. The English and French lines are not a fixed number of syllables, even by the most generous reading, and instead rely on stresses (usually four). This stress-based meter was incredibly old-fashioned by 1400; Langland’s “Piers Plowman” from 1360 was stress-based according to its Anglo-Saxon roots, but 20 years later Chaucer was strictly counting his syllables in the continental style [9, 10].

I believe that our poet began in continental style, found it too difficult, and ditched it. The first stanza is a slightly different structure from the rest of the poem:

A celuy que pluys eyme en mounde,

Of alle tho that I have found,

Carissima,

Saluz od treye amour,

With grace and joye and alle honour,

Dulcissima.

With the exception of line 4, which was evidently mangled by the scribe (that should be some version of <ottreyer> ‘to grant’) [11], this is a clean stanza of aa8 b4 cc8b4, the same stanza form used by Nicholas Bozon (fl. ca. 1320) in his famous work “La Plainte d’Amour.” Interestingly, Bozon wrote exclusively in Anglo-Norman French, though he lived the whole of his life (that we know about) in England [12].

Beginning with the second stanza and continuing through both poems, the poet reverts to counting stresses rather than syllables, and he reduced the syllable count in the Latin lines to three, with one stress. If Chaucer had been his teacher, I doubt he would have received a very good grade!

Since Chaucer was writing English while adhering to a syllable count, and French authors had already been doing it for years (Marie de France wrote in the 12th c. and used strict octosyllabic lines) [13], I chose to “fix” his structure back to the octosyllables he started with for the English and French lines. After playing with the Latin, I decided that the flow of the three-syllable line was superior to the four-syllable line, so I used aa8b3cc8b3 as my stanza form.

Having now selected a syllable count, I was faced with the joys of late Middle English and late Middle French, both of which were rather free when it came to counting syllables. By the 15th c., terminal <e>s were pronounced less, though in some usages, especially poetic ones, French retained the option of pronouncing terminals up to 1600, especially where a doubled consonant (and most especially a double-L) precedes the terminal <e> and a consonant begins the following word [14]. Note in the stanza above, the word <alle> is given two syllables in line 2 where it is followed by <tho>, but only one in line 5, where it is followed by <honour>, effectively an initial vowel.

Chaucer in some cases treated this freedom as a license to cheat. For example, in line 677 of the Knight’s Tale, he clearly uses <welle> as one syllable when one would expect two, and he drops an article for convenience:

Now up, now doun, as boket in a welle

Could I do less? In the end I found enough evidence of Chaucer’s preference for a modern expected syllable count that I used it exclusively, so the English lines may be read as you would modern English. I have also picked up Chaucer’s habit of dropping articles and prepositions where I needed to.

The same cannot be said for French. My writing model for the French lines was the work of Christine de Pizan (1363- ca. 1430) [15]. Her poetry leaves no doubt that the pronunciation of terminals was still expected for certain words, including most words ending in <-es> and <-elle>. Interestingly, words ending in <-ille> like <fille> ‘girl’ and <ville> ‘town’ typically represented only one syllable. Words ending in <-esse> sometimes represented an additional syllable if the word appeared within a line, but rarely at the end of a line. I have tried to follow these tendencies in the structure of my French lines. One notable exception was the phrase <en ycelle> ‘besides’; the expected spelling elsewhere in Middle French was <icel>, so I did not give it a sounded terminal [16].

With respect to rhyme, I noticed something odd about our mystery poet; his knowledge of French seems to have come from written, rather than spoken, French. He limited his rhymes to words that looked like they rhymed, whether they actually did or not. For example, he rhymes <charite> with <be>, which even in 1430 would have had markedly dissimilar pronunciations, but they both end in pronounced <e>s, so that was enough for our boy.

Now here again, Chaucer was happy to do this as well; in the Nun’s Priest’s Tale, he rhymes the name “Chaunticleer” with several different words, some of which tended towards rhyming with <ear> and some which tended to rhyme with <air>, even in 1400. (It’s all down to the Great Vowel Shift, a discussion of which is way beyond the scope of this documentation!) I decided to adopt his practice for my poem, so while some rhymes may appear inexact, they look like they rhyme, which was evidently expected practice for the time.

As far as poetic devices, I had another problem. Probably due to a greater familiarity with English, virtually all the similes are in the English lines, while most of the alliteration is in the French lines. Since my subject piece was simile-heavy, I chose to give each riddle a half stanza rather than the single line used in the original couplet form (see Appendix 2). That allowed me to keep the similes mostly in the English lines, using the French lines to expand the characterization (while sneaking in some alliteration).

For characterization, I decided to paint some shades of grey on the devil. If you pay attention to some of the French lines, you’ll see that the devil is giving the maiden occasional hints. When he asks her what is stronger (worse) than death (answer: pain), he asks if she learns from her suffering, putting the idea of pain in her mind. Likewise, he calls her attention to the fabric of her gown when the answer to “What is softer than flax” is “silk.” In the meantime, he insults her as much as possible, because after all, he is the devil. The maiden is strong in her faith, and has no problem standing up to the devil. In the end, she calls him by name, which was widely believed to give you power over a demon [7, 8].

The mystery poet did something very odd in the first half of the last stanza of the first poem; he inverts the language order: first English, then French. Every other sequence is ordered French, English, Latin. I believe this piece was intended to be performed aloud, and the inversion was to alert his audience that he was coming to an end (or at least a change of character). Perhaps he needed to wake them after all the platitudes. I felt that the maiden deserved the inversion in my poems; when she triumphantly names and defeats the demon, it is an emotional high point, and the inversion of line order supports that. Besides, it will be much easier to spit out “Satan!” in the tone it deserves in English.

Materials

Since my words are my materials, I got them from my models. Every English word was found in the Canterbury Tales, and every French word was found in the works of Christine de Pizan (exceptions noted below). Happily, I am familiar enough with both sources to be able to make a fair guess at spelling when looking for a word, but a few things were unexpected. Since I am familiar with modern French, I was surprised to learn that the verb forms for several of the irregular verbs like <savoir> ‘to know’ were almost exclusively the forms used in the modern language for the subjunctive mood. In a work where one character is constantly asking the other if she knows something, this got to be a little annoying until I figured it out [17].

In a few cases for the French, I got different forms of a word from the Dictionnaire du Moyen Francais (1330-1500), e.g., a second person conjugation where I could only find a third, but nearly every word was taken directly from Christine de Pizan’s work. Thankfully, she used a lot of words. Rarely, I had to get a word entirely from DMF like <riz> ‘rice’ because Christine didn’t write much about cooking!

The English words are entirely from Chaucer. I learned some interesting things about his spelling choices; for example, the word <thought> had the modern spelling exclusively when used as a noun (as I have), but was spelled exclusively <thoughte> with a terminal <e> when used as a verb. I therefore made sure that I not only found the word, but that it was used as the same part of speech.

Online resources are a fabulous boon, but unfortunately they aren’t very reliable for spelling. Helpful editors believe they are improving a transcription with spelling changes and punctuation or accents that didn’t appear in the original orthography. Happily, both Chaucer and Christine de Pizan’s work is now available online as images of original manuscripts [18, 19], so when I suspected something had been edited, I was able to check a true source. Besides the things I expected, like adding accents to the French and changing <I>s to <J>s, I caught an occasional transcription error. (Trust but verify.)

Based on “the Queen’s Manuscript” of Christine’s work [18], I have observed the following orthographical rules from the manuscript:

There are no accents. There are no <J>s.

There are virtually no capitals, even of <dieu> ‘God’ and <iesucrist>, except at the beginning of a line.

Any <U> or <V> beginning a word becomes <V>. Any <u> or <v> within a word becomes <u>.

My Latin lines I got from a dictionary [20]. Unlike languages in common use that change and grow, “dead” languages like Latin do not become corrupted by the introduction of modern or borrowed words, so I didn’t feel any further scrutiny was necessary to be sure all my Latin words were appropriate to the time of the piece.

Special Problems

I understood that this was going to be a very involved project, but I initially thought that some of it would be straightforward; after all, Latin grammar is all about endings, so end rhyme should be no problem! Sadly, it’s got to be the same case, the same voice, and not irregular. I learned my lesson with my first word, aenigma, which I initially made plural as <aenigmae> until I realized it is a 4th declension noun and therefore the correct plural is <aenigmata>. So much for the easy part! I also picked up a little grudging admiration for the mystery poet, because he really tried to have the lines make grammatical sense across the languages. So when he uses an infinitive form of a Latin verb, he truly means it to be read as, for example, “to love.” That hugely limited my word choices at times.

Also, rhyming two languages from different linguistic families is problematic. End sounds like <-ed> that are very common in English turn out to be quite rare in French, especially when it has to look like it rhymes (so <laide> ‘ugly’ is out). And the source material from the Rawlinson manuscript was chock full of <-ed> words.

Presentation

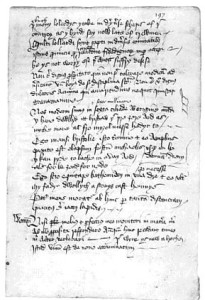

I embraced the concept of the poem transcribed among the household documents, or after the fashion of a school boy. The Rawlinson manuscript is full of pages that look like this, complete with pen wipes and marginalia:

I don’t intend you to evaluate the handwriting, but I wanted to put you in mind of the person, perhaps a schoolboy at his desk, who read an interesting poem, grabbed a scrap piece of vellum and took it down so he could wonder at it later. (The transcription was made on vellum with a dip pen in India ink.)

Okay, then I was silly, stuck a feather in my cap and called it, er, sprinkled it with macaroni. By the time I was done with this, I was more than ready for a little silliness!

Bibliography and Notes

[1] Cambridge University Library MS. Gg. 4. 27, part I, ca. 1430.

[2] Carpenter, Christine, ed. The Armburgh Papers: The Brokholes Inheritance in Warwickshire, Woodbridge: The Boydell Press, 1998, p. 155-6.

[3] Saunders, Corinne, ed. A Companion to Medieval Poetry, Oxford: Blackwell, 2010, pp. 280-282 in the essay “Macaronic Poetry” by Elizabeth Archibald.

[4] John M. Manly and Edith Rickert, The Text of the Canterbury Tales Studied on the Basis of All Known Manuscripts, (Chicago, 1940), I, 187. According to Manly and Rickert, based on certain eccentricities of spelling and letter formation, the scribe was a foreigner, possibly from Flanders.

[5] “Carmina Burana” at Bibliotheca Augustana (WWW: Bibliotheca Augustana), 1996.

https://www.hs-augsburg.de/~harsch/augustana.html

[6] Rawlinson MS. D. 328, Bodleian Library, before 1445.

[7] Child, Francis James, The English and Scottish Popular Ballads, 5 vols., NY: Cooper Square Publications, 1965 [originally published 1882-88], vol. I, p. 1.

[8] Orme, Nicholas, Medieval Children, London: Yale U. Press UK, 2001, pp. 144-148.

[9] Langland, William, “The Vision of Piers Plowman,” Prologue, WWW: Electronic Text Center, University of Virginia, 2005.

https://etext.lib.virginia.edu/toc/modeng/public/LanPier.html

[10] Chaucer, Geoffrey, The Canterbury Tales, (WWW: Electronic Literature Foundation), 1999-2007.

https://www.canterburytales.org/

[11] Spitzer, Leo, “Emendations Proposed to De Amico ad Amicam and Responcio”, in Modern Language Notes, Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, volume March, 1952, pp. 150-155.

[12] Purdie, Rhiannon, Anglicizing Romance: Tail-Rhyme and Genre in Medieval English Literature, Cambridge: D.S. Brewer, 2008, pg. 52.

[13] De France, Marie, various works at Wikisource (WWW: Wikisource), 2009.

https://fr.wikisource.org/wiki/Marie_de_France

[14] The defining instance of the villanelle, “J’ai Perdu Ma Tourterelle” by Jean Passerat (1534-1602) makes frequent use of pronouncing the terminal syllable, typically, as in <touterelle> ‘turtle-dove’, where a doubled consonant precedes the terminal <e>.

[15] De Pizan, Christine, various works at Project Gutenberg (WWW: Project Gutenberg), 2003-2010.

https://www.gutenberg.org/wiki/Main_Page

[16] Dictionnaire du Moyen Francais (1330-1500)

Available online through Nancy Universite:

https://www.atilf.fr/dmf/

[17] Pope, Mildred Katherine, From Latin to Modern French (with especial consideration of Anglo-Norman), London: Butler & Tanner, 1952, p. 344.

[18] De Pizan, Christine, “The Making of the Queen’s Manuscript” (WWW: Edinburgh University Library), 2010. Manuscript London: British Library, Harley MS. 4431, before 1414.

https://www.pizan.lib.ed.ac.uk/

[19] Chaucer, Geoffrey, The Canterbury Tales, in “Guide to Medieval and Renaissance Manuscripts in the Huntington Library” (WWW: Sharon K. Goetz), 2003. Guide text, San Marino: Huntington Library, 1989. Manuscript, San Marino: Huntington Library, EL 26 C 9, ca. 1410.

https://sunsite3.berkeley.edu/hehweb/EL26C9.html

[20] Collins Latin-English English Latin Dictionary, London: Collins, 1966.

Woodcut gratefully lifted from:

Matterer, James L, “Medieval Macabre” (WWW: James L. Matterer), 2000.

https://www.godecookery.com/macabre/gallery4/macbr109.htm

The two poems, “De Amico ad Amicam” and “Responsio” can be read in full here:

https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Lines_from_Love_Letters

Here is the text from note [6]:

Inter diabolus et virgo

| 1 | Wol ȝe here a wonder thynge Betwyxt a mayd and þe fovle fende? |

| 2 | Thys spake þe fend to þe mayd: ‘Beleue on me, mayd, to day. |

| 3 | ‘Mayd, mote y tin leman be, Wyssedom y wolle teche the: |

| 4 | ‘All þe wyssedom off the world, Hyf þou wolt be true and forward holde. |

| 5 | ‘What ys hyer þan ys [þe] tre? What ys dypper þan ys the see? |

| 6 | ‘What ys scharpper þan ys þe þorne? What ys loder þan ys þe horne? |

| 7 | ‘What [ys] longger þan ys þe way? What is rader þan ys þe day? |

| 8 | ‘What [ys] bether than is þe bred? What ys scharpper than ys þe dede? |

| 9 | ‘What ys grenner þan ys þe wode? What ys swetter þan ys þe note? |

| 10 | ‘What ys swifter þan ys the wynd? What ys recher þan ys þe kynge? |

| 11 | ‘What ys ȝeluer pan ys þe wex? What [ys] softer þan ys þe flex? |

| 12 | ‘But þou now answery me, Thu schalt for soþe my leman be.’ |

| 13 | ‘Ihesu, for þy myld myȝth, As thu art kynge and knyȝt, |

| 14 | ‘Lene me wisdome to answere here ryȝth, And schylde me fram the fovle wyȝth! |

| 15 | ‘Hewene ys heyer than ys the tre, Helle ys dypper pan ys the see. |

| 16 | ‘Hongyr ys scharpper than [ys] þe thorne, Þonder ys lodder than ys þe horne. |

| 17 | ‘Loukynge ys longer than ys þe way, Syn ys rader þan ys the day. |

| 18 | ‘Godys flesse ys betur þan ys the brede, Payne ys stronger þan ys þe dede. |

| 19 | ‘Gras ys grenner pan ys þe wode. Loue ys swetter þan ys the notte. |

| 20 | Þowt ys swifter þan ys the wynde, Ihesus ys recher þan ys the kynge. |

| 21 | ‘Safer is ȝeluer than ys the wexs, Selke ys softer þan ys the flex. |

| 22 | ‘Now, thu fende, styl thu be; Nelle ich speke no more with the! |