by Adelaide de Beaumont (Lisa Theriot)

I am often asked whether “filk” is a period practice. Not fantasy-themed original works, mind you, but pieces that “borrow” from others. The answer is yes, though there are modern mundane considerations of copyright that our period counterparts didn’t have to worry about. But there is no denying that our forebears were just as capable of plagiarism as we are, not that they would have thought of it as such.

You can’t copyright a form or idea, even today. Sheesh, if someone held a monopoly on love songs, or sonnets, we’d be pretty strapped. We wouldn’t have half the ballads we have if people hadn’t lifted the plots from literary or foreign sources. Chaucer and Shakespeare recycled most of their plots from Boccaccio and other sources, and Boccaccio got most of his stories reading from classics like Ovid. There is absolutely nothing wrong with borrowing story elements and formats, and it makes you no less a creative artist for finding “inspiration” where you may. The gray area begins where you use an entire melody, or large enough sections of lyric that the original piece is readily identifiable despite your changes. But you won’t be the first to do it.

The Elusive Melody and “Contrafacta”

Many people complain that they just can’t write music, so they opt for filk as an easy way of procuring a tune. What they really mean is that the words come more easily to them than the tune, and I feel their pain; the same is true for me. But unless you are truly tone-deaf, you are probably capable of producing a melody, with effort. Try it, you’ll like it. That said, there is ample period evidence for “tune borrowing.” I have never found a discussion in period of copyrighting a melody. Tune books, for lute or virginal especially, were licensed for printing purposes, but I doubt seriously that someone at the Stationers Company checked all the tunes to make sure they weren’t the same ones some other guy licensed the previous week. Heck, I’m not sure anybody at the Stationer’s Company in 1580 could even read music. Few people were music-literate, so most broadsides (printed song sheets) just said “to the tune of…” Evidently, the authors were confident concerning the wide knowledge of popular tunes, which is really pretty amazing in a time before radio and recorded audio media.

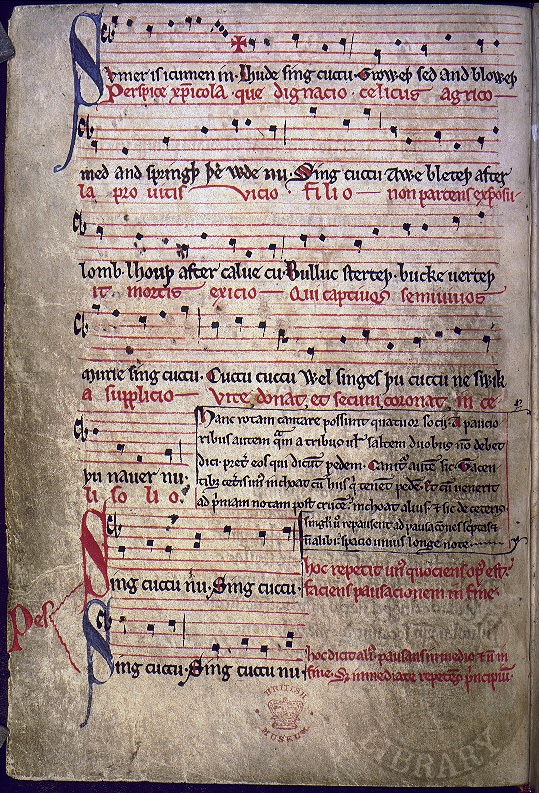

I like to think of period filk as having two main flavors. The first is often called contrafacta (or contrefait in French—yes, this is the root of the word “counterfeit”). A contrafactum was a piece where an entirely different lyric was substituted for the original. Often, a piece was borrowed from one sphere into another, such as using a melody from sacred music for popular music or vice versa, via the complete substitution of the lyric [1]. The medieval hit “Sumer is Icumen In” was a contrafactum. The manuscript that provides our earliest copy of the song (Harley MS 978, British Library, ca. 1240) bears the melodic score along with two complete sets of lyrics, the secular song in black ink and a religious piece in Latin on the Passion of Christ below it in red ink [2]. The secular lyric is clearly the original, at least for this manuscript, since the illuminated initial is “S”. The two sets of lyrics are totally unrelated:

Sumer is icumen in

Lhude ſing, cuccu

Groweþ ſed and bloweþ med

And ſpringþ þe wde nu

Sing cuccu

(Here ſ is ‘long S’, þ is thorn, an old way to write TH, and w is mostly a vowel–we call it double-U, right?)

Perspice χρicola (read christ-icola)

Que dignacio

Celicus Agricola

Pro vitiſ vicio

Filio

(Here χρ is chi-rho, Greek letters used to represent ‘Christ’. The Latin translates as ‘Christian, see what condescension, Heavenly Husbandman for the vines’ sake’.)

The practice was carried out for secular-to-secular conversion as well. Evidently, hawkers of 16th century broadside sheets found it easier to sell “songs” to people (who presumably didn’t read music) if they could be sung to existing and well-known tunes. Consider an example from the collection A Handefull of Pleasant Delites printed in 1584, “A Sonet of two faithfull Louers, exhorting one another to be constant. To the tune of Kypascie [3].” This was a dance tune, actually, Chi passa per questa strada, but not surprisingly for an Italian song, the words were in Italian. Another example from the same collection is given as, “An excellent Song of an outcast Louer. To, All in a Garden green.” “All in a Garden Green” definitely had words, but there are no obvious similarities between the original and the filk [4, 5]:

| All in a garden green, Two lovers sat at ease: Withdrawn where they could scarce be seen, Among the leafy trees. |

My fancie did I fixe, In faithful forme and frame: In hope ther shuld no blustring blast Haue poer to moue the same. |

This is true contrafactum, the complete substitution of a new lyric for the old. But armed with these two examples, we can see what contrafacta do, which is structure a new lyric ON the original lyric, NOT ON THE MUSIC. Look at the lyrics of Sumer and its filk, and bear in mind the terminal Es are pronounced in Middle English. You get:

Su-mer is i-cu-men in, lhu-de sing cuc-cu, 7 syllables and 5 syllables

Gro-weth sed and blo-weth med and springth the w-de nu, 7 syllables and 6 syllables

Sing cuc-cu, 3 syllables

Per-spi-ce Christ-i-co-la que dig-na-ci-o, 7 syllables and 5 syllables

Ce-li-cus ag-ri-co-la pro vitis vicio, 7 syllables and 6 syllables

Fi-li-o, 3 syllables

Now look at the music. There are NINE notes over 7 syllables in the first line, and you sing i-i-in. But the Latin lyric could well have used those syllables, especially considering how many Latin words triple easily, like filio. But they DIDN’T. You sing Christ-i-co-la-a-a just like you sang i-i-in.

How about All in a Garden Green?

All in a garden green, two lovers sat at ease, 6 syllables and 6 syllables

Withdrawn where they could not be seen, 8 syllables

Among the leafy trees, 6 syllables

My fancy did I fix, in faithful form and frame, 6 and 6

In hope there should no blust’ring blast, 8 (note they dropped that E, blus-tring)

Have power to move the same, 6 (trust me here—in period power, fire and a number of other words that we consider two syllables were considered ONE)

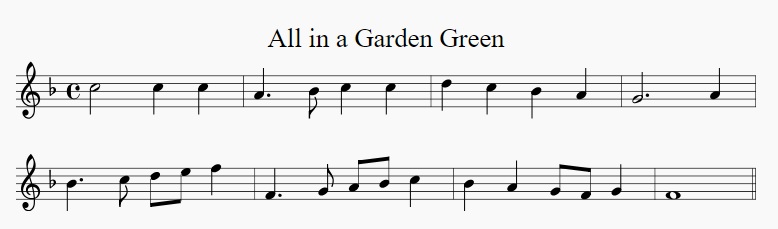

Here’s the music (standard notation) [4]:

Six notes, six notes, TEN notes, SEVEN notes. Both lines three and four have tied notes that you trill over a single syllable, ‘they’, ‘seen’, and ‘leaf-‘ in the original, and ‘should’, ‘blast’, and ‘move’ in the filk. They had a syllable in the filk they had to cop, blus-ter-ing to blus-tring, and they had a spare note, and they DIDN’T USE IT. They stretched ‘blast’ over two notes. I presume that this phenomenon had to do with the general lack of music-reading ability of most people, and writers of new works assumed that people would plug the new words into the place of the old words and carry on. But I cannot give you an example of a period filk where the words line up with the notes of the music rather than the original lyric, assuming there was one. And if there wasn’t? Some tunes, like Chi Passa/Kypascie were so altered musically by their journey to England, that expecting the Italian to line up is hopeless, even if you count all the syllables that singers of Italian customarily leave out while singing. We’ll talk about Kypascie again later.

Some formats (like the eight-syllable-lined quatrains of a piece like “Greensleeves”) were incredibly common, and authors didn’t even feel the need to pick out a tune for the consumer to sing to. Several songs in “Delites” have completely open direction, such as, “A proper sonet, Intituled: I smile to see how you deuise. To anie pleasant tune [6].” I’ve never known anyone in the SCA to write a filk and sing it to several different tunes, but it’s both possible and terribly period. As is often noted, you can sing “Amazing Grace” to the tune from “Gilligan’s Island” and vice versa; as long as your structure is the same, the tune will fit naturally. Try singing “Greensleeves” to “Yankee Doodle” and vice versa. I know, it makes your head hurt, but it can be done.

If the only way you’ll write songs is to use a tune from elsewhere, then by all means go ahead, but remember that the broadside sellers didn’t have the owners of the original tunes coming after them with lawyers. Find a period dance tune or some other period song, or at the very least a song no longer under active copyright defense. Copyrights generally run for life of the author plus 70 years, so anything written before 1900 is probably fine [7]. That leaves you a lot of traditional material. Many people use Christmas carols. Personally, I find I can’t concentrate on new lyrics when I know the old ones so well, but therein lies one of the chief dangers of filk (after the lawsuits): it’s tough for anyone to pay attention to your lyrics when they’re playing the original lyrics in their head. There’s a better way, and it’s period, too.

Frankenstein melodies, piecemeal contrafacta

So, instead of borrowing an ENTIRE melody, what if you borrowed a line from one place and the next line from another? People might start to think the tune was familiar, but as soon as you diverge from the expected, most people will stop thinking about it.

Juliet, in what would be Act III, scene v eventually, says in the 1597 folio of Romeo & Juliet [17]:

Some say the Larke and loathed Toad change eyes,

I would that now they had changd voyces too:

Since arme from arme her voyce doth vs affray,

Hunting thee hence with Huntsvp to the day.

“Huntsup” is a reference to a song that dates to the reign of Henry VIII referred to as The Hunt is Up, Huntes Upp, The King’s Hunt, and others. This song was so popular that versions of it exploded. Chappell remarks, “It seems to have been almost, if not quite, the most popular of the old ballad tunes, and popularity would be almost sure to bring about alterations in a tune…” [18] Let’s think about that for a minute. In period, everybody knowing the song actually leads to MORE changes in both the lyric and the tune. One of the reasons we can date this song to early in the 1500s is that a guy was arrested, and I kid you not, for singing a filk of this song in 1537 [11]. It was so popular that “huntsup” passed into English as a general term for songs to wake people, though at some point the French reveille ‘wake up’ supplanted it.

By 1600, there were dozens of variations on Huntes Upp, as well as new compositions intended for the same purpose, so finding what the original tune or lyric was is almost impossible. But the sweet thing is, it doesn’t matter. What’s the tune to Huntes Upp? The one you know. The really wild thing is that as lute and virginal players notated variations that required virtuoso playing, only the barest bones of a melody remained, and key, time signature, pacing, everything we customarily identify about a piece of music was altered as people saw fit. Even tunes for singing were altered as people liked one bit more than another. One generally accepted spin of the Huntes Upp tune was printed in 1600 as “Peascod Time,” or the time for gathering field peas. People who dance European dance in the SCA will recognize it from Playford under the name “Gathering Peascods.” Here’s the thing that will rock your world: the first two lines of Gathering Peascods are identical with the first two lines of… wait for it… All in a Garden Green. The circa 1600 lyrics for Peascod Time do NOT match the structure of AiaGG, they match the structure of the older lyrics for Huntes Upp. AT SOME POINT, but before 1600, somebody decided they liked that strong downbeat at the beginning that meant 6 syllables were a better fit for the first line than 8 (“The hunt is up, the hunt is up” and “In peas-cod time, when hound to horn”) and off they ran. Were the second two lines of AiaGG taken from a different version of Huntes Upp? From another song? Were they original? Playford’s Peascods has extra lines as required for features in the dance, that don’t match Huntes Upp OR AiaGG. Where did those come from?

This is also where pieces like Kypascie come in. The Italian version started as part of a commedia, but it came into England as a galliard. If you’re not familiar with a galliard, it tends to have a strong level beat plus fiddly bits, so you have a variety of choices of timing. Presented with this, the author of the filk opted for a very regular set of syllables, much more so than the Italian lyric [4]:

The famous Prince of Macedon (8)

Whose wars increst (increased) his worthy name (8)

Triumphed not so, when he had won (8)

By conquest great, immortall fame (8)

As I reioice, reioice (rejoice) (6)

For thee, my choice, with heart and voice, (8)

Since thou art mine, (4)

Whom, long to loue, the Gods assigne. (8)

This will not fit the original Italian music, and I have trouble fitting it into the English “Galliarde qui passe” (search “William Byrd – Qui Passe for my Lady Nevell” and see if you can figure it out), but I can sing it to Greensleeves (or Yankee Doodle) and barely blink. There was very likely a more regular tune, and maybe even a less bouncy dance to go with it, extant before 1600 such that these very regular lines made sense. But because they ARE regular, they are easily shaped into another tune than the one intended. The more you make your lyric fit into every tiddle and jot of a complicated melody, the more you are stuck with that melody, and apparently that’s not a period mindset.

We are forced to conclude that people were even more likely to tinker with tunes than they were with lyrics, with even less reference to the source. Accordingly, I think it reasonable and likely that if you took one line of music from one source and another from another, it would be a completely reasonable thing to do, assuming the pieces weren’t in radically different styles or modes. I wouldn’t mix AiaGG with Greensleeves, for example. But Fortune, My Foe and Pastyme With Good Companye are musically very similar, and you could share freely between them as you like.

As with Kypascie, If you have enough facility with music, try singing a song in a different time signature. The most common tune for the Huntes Upp is in 6/8, and AiaGG is in 4/4. Take it from major to minor. Honest, serious composers are still doing this; Gustav Mahler’s Symphony #1, first performed in 1889, has a movement (the third) that is a funeral march, and as you listen you realize it’s “Frère Jacques” taken into the minor. A couple of tweaks, a new lyric, and it’s a new song.

Parody, Pastiche, and SCA-style filk

SCA filk often uses a LOT of the original lyric of the song as well as the tune. If I can tell by the lyrics alone what song you filked, it’s a definite problem in the creativity department and a potential problem of legality. I don’t need a tune to guess what “Hark the herald ” is modeled on. You’d be stunned how little it takes. A local person had a filk for which the first line was “Almost Asgard, Ansteorra,” and I explained to them just how fiercely the rights for “Take Me Home, Country Roads” were defended. When it’s 80% of their livelihood, they WILL come after you, whether you mean to profit by it or not. Why waste your time on something that will have to go away once you receive the ‘cease and desist’ letter?

When cautioned against outright plagiarism, some will respond, “But there’s an exemption in copyright law for parody!” thus demonstrating they don’t understand what parody actually means. In order to qualify as a parody, small bits of a published work must be used to create satire, usually satirizing the work itself. So unless you intend to make fun of a song, you’re probably not writing parody [8]. About the only example of an SCA filk I’ve heard that qualifies is the terrible “Let There Be Wars on Earth” sung to the terrible “Let There Be Peace on Earth.” It’s a clear parody, an attempt to skewer a schmaltzy song by turning it on its head; however, since I think the author(s) changed something like 17 words from the original it’s still actionable as copyright infringement. Even parodies can’t use substantive portions of the original work without paying royalties [8].

Another term for eerily similar material is pastiche, which is a work deliberately undertaken in the style of another work (or author). Most fan fiction is pastiche. Pastiche is NOT granted a copyright exemption, so if you’re using a lot of the original work, you’d better be sure that you have the original author’s permission or that they’ve been dead too long for anyone to care. Stephanie Barron’s Jane Austen series is a great example, because she uses a lot of text from Austen’s published works. But Jane died in 1817, so no copyright defense will be forthcoming from that quarter.

That leaves us with filk wherein the author is neither trying to ridicule a work nor produce a new work in a recognizable style; rather, they simply found a cool song and want to bend it to their own ends. Such a song is “Farewell to Ansteorra,” Alaric ap Morgan’s filk from “Farewell to Nova Scotia.” Fortunately “Nova Scotia” was itself a filk of “The Soldier’s Adieu” by Robert Tannahill (1774-1810), so no one is coming for royalties, at least for the tune. Not so for many other songs I’ve encountered in the SCA. If you wrote some new words to a Christmas carol, I might not give you high marks for creativity, but at least no one is likely to be sued (assuming it’s a traditional carol and not “White Christmas”). If you’ve published a heavily derivative work based on a song in the Sony catalog, I hope you have no assets. (If I haven’t scared you enough yet and you are given to filking contemporary songs, please read Appendix 1.)

So that style of filk is modern, huh? Sadly again, no. The second major type of period filk can be classed as “jumping on the bandwagon.” These were almost musical conversations or one-upmanship competitions. The first one would come out, then someone else would write their own take. Sometimes the original author would think of something new to say and jump back in.

The following songs were licensed with the Stationers’ Company, granting the licensees the RIGHT to make COPIES (the origin of copyright) [9, 10]:

William Pickering, 1565-6 “Row well, ye mariners”

William Pickering, 1565-6 “Row well, ye mariners, moralized”

John Alldee, 1566-7, “Stand fast, ye mariners”

John Alldee, 1567-8, “Row well, ye mariners, moralized, with the story of Jonas”

John Alldee, 1567-8, “Row well, Christ’s mariners”

Alexander Lacy, 1567-8, “Row well, God’s mariners”

John Sampson, 1569-70, “Row well, ye mariners, for those that look big” (No idea.)

These works all presumably used a portion of the original lyric, which seems to have been lost along with the derivative works. The tune, however, was popular for dancing and survived to be applied to a number of totally unrelated works. Beginning in 1570, there was a series of anti-Papal sentiment songs given as sung to the “Row well” tune, though they seem to have no reference in the lyric to the original. Likewise Delites references the tune for use with an obviously unrelated love song.

In the case of “Row well” it seems that the various writers were trying to out-moral the other guy on this song. This is hardly surprising given several laws that were passed encouraging writers to toe the party line as far as political and religious matters were concerned. The guy I referenced above who was arrested for singing a filk to Huntes Upp was arrested not because he was infringing anybody, but because the filk was political in nature and insulted the wrong people [11]. The author/competitors were obviously also trying to make a shilling or two off an apparently wildly popular song. Some things never change!

A similar publication bandwagon was launched concerning “Greensleeves”. Richard Jones received a license in 1580 for, “A new northern dittye of the Lady Greene Sleeves.” Jones was evidently tardy in getting his license, because on the same day that Jones received his license, a license was granted to Edward White for, “A ballad, being the Ladie Greene Sleeves Answere to Donkyn his frende.” Twelve days later a license was granted for, “Greene Sleeves moralised to the Scripture, declaring the manifold benefites and blessing of God bestowed on sinful man.” Three days after that, Edward White had, “tolerated unto him by Mr. Watkins, a ballad intituled Greene Sleeves and Countenance, in Countenance is Greene Sleeves.”

Two months later Richard Jones must have decided other people were making money so he should make some more, and licensed, “A merry newe Northern Songe of Greene Sleeves, beginning ‘The bonniest lass in all the land.'” Two months later, people were obviously tiring of the song; William Elderton licensed, “Reprehension against Greene Sleeves.” Six months later Edward White jumped back in with:

“A ballad intituled-

Green Sleeves in worne awaie,

Yellow Sleeves come to decaie.

Blacke sleeves I holde in despite,

But White Sleeves is my delight [12].”

Eventually Green Sleeves turned into a snappy dance tune (appearing in the 7th edition of Playford published in 1686); the resulting lyric (from Sportive Wit, or the Muses’ Merriment, 1656) is, as you can see, quite bawdy:

Greensleeves and pudden-pyes,

Come tell me where my true love lyes,

And I’ll be wi’ her ere she rise:

Fidle a’ the gither!

Hey ho! and about she goes,

She’s milk in her breasts, she’s none in her toes,

She’s a hole in her a—, you may put in your nose,

Sing: hey, boys, up go we!

Green sleeves and yellow lace,

Maids, maids, come, marry apace!

The batchelors are in a pitiful case

To fidle a’ the gither.

You could feel for Richard Jones, though since he’s in there twice himself, presumably it was business as usual for the time. It’s also important to note that these were the licensees, not necessarily the authors. Members of the Stationer’s Company often bought works from authors and reaped virtually all the profit from the sale of the copies.

Some people consider SCA original works fair game for filking. From a legal standpoint, this is certainly safer than filking Beatles’ songs; few SCA songwriters even bother to copyright their work, and none that I know of have a major label recording deal. I have seen filks of this second type written based on SCA original works to good effect. I’ve also seen some really bad ones. Someone once told me that they didn’t think a song of mine was long enough, so she offered to write a few more verses; none of her ideas had the slightest reference to the main storyline. I declined. But she did the right thing and asked first. Did I mention that mundanely, she’s a lawyer?

Remember that the SCA is a small world. It’s probably a bad idea to appropriate the material of someone you might run into at Pennsic. Master Ivar Battleskald requested for many years that his words to “Born on the Listfield” not be written down, so how do you think he felt hearing “Bored on the Listfield,” “Drunk on the Listfield,” and the host of other bad filks of his work? Given his love of the folk process, he might have felt great; some SCA writers have a “Fly, be free!” attitude about their work. Others don’t. Be a gracious and honorable gentle and Ask First.

Copyright—a modern concept?

Au contraire. Legal precedent concerning the RIGHT to COPY a written work belonging to someone else is ancient. Medieval scribes would likely have been familiar with the cautionary tale of Saint Columba [13, 14]:

Columba was a 6th century Irish monk serving under an abbot named Finnian. Finnian had been to Rome and acquired a copy of the Gospels; Columba asked to copy the manuscript but Finnian refused. Columba, being a proud man, wouldn’t take “no” for an answer, so he got up in the middle of each night and copied a bit of the manuscript. Just before Columba completed his copy, Finnian discovered what Columba was doing and demanded the copy; Columba refused and retreated to the country of his tribe.

Finnian appealed to Diarmait, the High King of Ireland, who summoned both to appear before him. After hearing the story, the King’s judgment was “To the cow, her calf; to the book, her little book.” Finnian had won, but Columba again returned to his tribe, this time to raise an army. Diarmait, angry that his judgment had been defied, marched against him. Columba’s forces prevailed, but two thousand men were killed; as penance Columba’s confessor told him to leave Ireland and win as many souls for Christ as had been lost in the battle.

Columba’s story illustrates why there was no need for much in the way of copyright control during the medieval period: the only way to make a copy was to do it by hand, for which few people had the skill or the time required.

The interesting thing about the Diarmait Decision is that the ownership of the content was assumed to belong to the person who owned the book. It’s not like Finnian wrote, or even translated the gospels.

After the invention of the printing press in the 15th century, however, the floodgates were opened. Governments initially tried to maintain control over printed matter, hence the licenses granted to people like Richard Jones and Edward White, but eventually enough people figured out how to print material on their own that laws covering intellectual property were enacted. Thus was born the idea that if an author can’t profit from his own work, what incentive does he have to create in the first place?

The Statute of Anne (1710) was titled, “An Act for the Encouragement of Learning, by Vesting the Copies of Printed Books in the Authors or Purchasers of such Copies, during the Times therein mentioned” and stated as its goal, “the Encouragement of Learned Men to Compose and Write useful Books.” This Act was a major change, because it specified ownership to an author (for unpublished works) [15]. During the period of the Stationer’s Company monopoly (1556-1695), Company members would buy manuscripts from authors but once purchased, would have exclusive right to print the work. Authors who were not members in the Company could not legally self-publish, nor were they entitled to royalties for works that sold well [16]. (So pity the poor guy from whom Richard Jones may have purchased “Greensleeves,” and whose name is lost forever.)

True, modern copyright has gone far beyond what the Statute of Anne ever intended. SoA specified a 14-year period of exclusive right; current law specifies the life of the author plus 70 years. Imagine if everything written before 1992 were in the public domain! (Sony would make even more money, because they’d still sell the CDs and they wouldn’t have to pay the artists…)

So Why Not Filk?

Most filk isn’t great. If you’re writing filk to modern songs, even if they’re not under copyright, don’t expect any better reception in an SCA Arts environment than someone who makes costumes out of polyester. You’re trading ease for quality and ambiance. And if local filk singers are the loudest, bards in general are branded with the same badge of inauthenticity.

There IS great filk out there. And I don’t mean so-called “original filk” as the term is sometimes applied to pieces by artists like Leslie Fish and Heather Alexander (or, you know, me). If both the melody and the lyric are original, the work deserves the respect any creative piece is due. No, I mean great filk in the categories I’ve described above. I’ve heard wonderful songs to extant tunes, both historical and modern. I’ve heard wonderful “bandwagon” filk written with the blessings of the original authors (in some cases to songs I would never have likely heard otherwise). I have heard more than one filk piece that I consider lyrically superior to the original. But I’m always a little disappointed when I find out a piece is filk (that is, when it’s not obvious from the start), especially of the latter type, and my appreciation is always somewhat lessened. After all, you didn’t rely solely on your own creativity. Worse, once a piece is revealed as filk, it creates an invitation for less educated and principled writers to move on to Beatles’ filks, so even good filk is fraught with peril.

But just as there is a place for wash-and-wear garb and waterproof camp gear, there is a place for some filk, especially upbeat pieces that appeal to a large audience. And appeal they do. But there is also incredibly enjoyable 100% period and traditional material out there, and much of it is in languages besides English. It’s crying out to be brought to an audience in such a way that they’ll LISTEN to it. And once the creative juices are flowing, it really is a short step from good filk to completely original work.

Bibliography and Notes

[1] Bukofzer, Manfred F., “Popular and Secular Music in England”, in The New Oxford History of Music 3: Ars Nova and the Renaissance, 1300-1540, ed. Anselm Hughes and Gerald Abraham, London: Oxford University Press, 1960, p. 108.

[2] “Sumer is icumen in” in Wessex Parallel WebTexts, ed. Bella Millett, WWW: English, School of Humanities, University of Southampton, 2003.

https://www.soton.ac.uk/~wpwt/harl978/sumer.htm

[3] Rollins, Hyder, ed., _A Handful of Pleasant Delights_ (1584) by Clement Robinson and Divers Others, Dover, 1965, (A reprint, the original was published in 1924.), p. 53

[4] Chappell, William, _Old English Popular Music_ (a new edition, with a preface and notes and the earlier examples entirely revised by H. Ellis Wooldridge), New York, 1961, original printed 1838, p. 79.

[5] Rollins, p. 46.

[6] Rollins, p. 52.

[7] Dates established by the “Sonny Bono Copyright Term Extension Act” (1998). If you’re having trouble sleeping, the full text of the Act is available online:

https://www.copyright.gov/legislation/s505.pdf

[8] In Campbell vs. Rose-Acuff Music, Inc. 114 S. Ct. 1164, (1994), the Supreme Court defined parody as, “the use of some elements of a prior author’s composition to create a new one that, at least in part, comments on the author’s works… If, on the contrary, the commentary has no critical bearing on the substance or style of the original composition, which the alleged infringer merely uses to get attention or to avoid the drudgery of working up something fresh, the claim to fairness in borrowing from another’s work diminishes accordingly (if it does not vanish)…” This case was the successful argument by 2 Live Crew that their rap rewrite of “Pretty Woman” constituted fair use as a parody by conjuring the spirit of the original work with the original first line of lyrics and characteristic opening bass riff but thereafter departing markedly from the Orbison lyrics, producing otherwise distinctive music. Since the woman “walking down the street” in 2 Live Crew’s version is definitely NOT pretty, the ironic effect is powerful. Contrast that with the case of Dr. Seuss vs. Penguin Books 109 F.3d 1394, (1997) wherein the Seuss estate was able to stop the printing of a satirical look at the O.J. trial titled, The Cat NOT in the Hat; in this case, the intent was to poke fun at the trial, not Seuss’ work, and the new work was held to be an infringement.

[9] The format of the dates (e.g., 1567-8) results from the business year and the calendar year being different. Until 1752, when shift from the Julian to the Gregorian calendar was made in England and the official year end established as December 31st, the end of the year for business and record-keeping purposes was March 24th.

[10] Chappell, pp. 127-8.

[11] Chappell, pp. 54-5. A royal proclamation of 1533 expressed a desire to suppress “fond books, ballads, rhimes, and other lewd treatises in the English tongue”, on the strength of which they started arresting people singing political songs. In 1543 an act was passed into law as follows:

“An Act for the advancement of true religion, and for the abolishment of the contrary… froward and malicious minds, intending to subvert the true exposition of Scripture, have taken upon them, by printed ballads, rhymes, &c., subtilly and craftily to instruct his highness’ people, and specially the youth of this realm, untruly. For reformation whereof, his majesty considereth it most requisite to purge his realm of all such books, ballads, rhymes, and songs, as be pestiferous and noisome. Therefore, if any printer shall print, give, or deliver any such, he shall suffer for the first time imprisonment for three months, and forfeit for every copy 10L., and for the second time, forfeit all his goods and his body be committed to perpetual prison.”

Scary, huh? Would you take a chance? There was a list of exceptions, including “all books printed before the year 1540, entituled Statutes, Chronicles, Canterbury Tales, Chaucer’s books, Gower’s books, and stories of men’s lives”. No ballads were exempted. Of course, since printing didn’t hit it big in England until shortly before 1500, “all books printed before the year 1540” isn’t as generous as it sounds.

[12] Chappell, pp. 239-40.

[13] Putnam, George H., Books and their Makers during the Middle Ages, 1476-1600, New York, 1962.

[14] Donnchadh O/ Corra/in & Mavis Cournane, “Annals of the Four Masters, vol. 1”, six volumes (WWW: CELT: Corpus of Electronic Texts: a project of University College, Cork, Ireland, 1997-98), entries M555-557. The Annals are a history of important events in Ireland. From the language used, these histories were written around 1200, so they reflect genuine medieval perspective though they relate events six centuries after they are meant to have taken place and cannot therefore be relied on as factual. https://www.ucc.ie/celt/published/G100005A/

[15] “The Statute of Anne” at The Avalon Project at Yale Law School, WWW:

The Lillian Goldman Law Library in Memory of Sol Goldman, 1996-2005.

https://www.yale.edu/lawweb/avalon/eurodocs/anne_1710.htm

[16] “Worshipful Company of Stationers and Newspaper Makers” in Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia, WWW: Wikipedia, 2005.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Worshipful_Company_of_Stationers_and_Newspaper_Makers

[17] The University of Victoria Shakespeare online.

https://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/doc/Rom_Q1/complete/

[18] Chappell, pp. 86-7.

Books Online I paid a lot for:

Chappell, William, Old English Popular Music, New York, 1961 [originally published 1838]. Melodies and lyrics to early popular songs in modern notation.

https://archive.org/details/oldenglishpopula02chapuoft

Percy, Thomas, Frederick James Furnivall, John Wesley Hales, Bishop Percy’s Folio Manuscript: Ballads and Romances, London: N. Trübner, 1868.

https://archive.org/stream/bishoppercysfol00halegoog#page/n8/mode/2up

Websites You Might Like:

Internet Archive. This is a gold mine, but it’s also kind of like the warehouse where Indiana Jones stashed the Ark of the Covenant. It’s best to use your search engines until you identify a work, then look here. There are complete period and near-period books of music here.

https://archive.org/

British Library Digitised Manuscripts. Again, too much to plow through, but you’ll find a wealth of period texts, music, etc.

https://www.bl.uk/manuscripts/

Bibliothèque nationale de France. Froissart’s Chronicles, Christine de Pizan, etc. The English-language version is fairly functional, so don’t be scared off just because you have no French.

https://www.bnf.fr/en/tools/a.welcome_to_the_bnf.html

Cantigas de Santa Maria for Singers. Everything you want is usually here: sheet music, lyrics, pronunciation guide, manuscript links.

https://www.cantigasdesantamaria.com/

DIAMM (the Digital Image Archive of Medieval Music).

https://www.diamm.ac.uk/

Folger Shakespeare Library. I sometimes have problems here asking to sign in, but if you around the corner to the LUNA Digital Image Collection, you should be able to browse freely.

https://luna.folger.edu/luna/servlet

Medieval Music & Arts Foundation. A little hard to navigate, but again, they have saved you huge amounts of time if you do some looking. Hit the Early Music FAQ page, and you’ll find things like a discography link for Guillaume Dufay, which has enough info (often including manuscript numbers!) to help you not only find a CD you might love, but the documentation to go with it.

https://www.medieval.org/

https://www.medieval.org/emfaq/composers/dufay.html

Medieval Primary Sources, Seminar X: Poetry and Song. This is from the U of Lancaster, and has incredible links and bibliography. Some things are annoyingly behind a ULanc wall, but if you go to, say, the discussion of the Agincourt carol, the links will take you right to the two extant manuscripts.

https://www.lancaster.ac.uk/staff/haywardp/hist424/seminars/10.htm

Monastic Manuscript Project. If you are looking particularly for sacred music, this site is an amazing shortcut to places that have medieval manuscripts available online. It doesn’t have a lot of detail for what you’ll find, and the links are often broken as places go behind pay walls, but on one of those days when you have time to go down a rabbit hole, it’s a treasure trove.

https://www.earlymedievalmonasticism.org/listoflinks.html#Digital

The Music of Thomas Ravenscroft. Presented by Greg Lindahl, there are facsimiles of much of Ravenscroft’s works, plus links to other interesting sites.

https://www.pbm.com/~lindahl/ravenscroft/

Outlaws and Highwaymen. The author (Gillian Spraggs) of a book by the same name has a great deal of her research material here, including original (un-spell-corrected!) text from the 1556 English translation of Thomas More’s Utopia. Also, not surprisingly, you’ll find good info for documenting outlaws and highwaymen, a favorite topic for SCA bards.

https://www.outlawsandhighwaymen.com/

Rhyme Zone. An online rhyming dictionary and thesaurus (any poet who says they don’t use a rhyming dictionary either lies or writes bad poetry). Best of all, there’s that search engine to the complete works of Shakespeare, allowing you to check for period word usage.

www.rhymezone.com

Sacred Texts Online. Okay, I know they have stuff on UFOs. But they also have good webbed translations (and a few originals, like Beowulf) of Arthurian, Celtic, and Norse works as well as studies thereon. Tiptoe through the trash and look for the treasure.

https://www.sacred-texts.com/

Traditional Tune Archive by Andrew Kuntz & Valerio Pelliccioni. LOTS of music, generally copyright-free under Creative Commons, but not much pre-1600. Mostly geared to fiddle tunes.

https://tunearch.org/wiki/TTA

Trobar, the website of Leonardo Malcovati. Much of the site is devoted to prosody and various fixed forms of poetry; if you’re looking for troubadour songs, just stick to that page. The rest is fascinating if you’re a poetry geek.

https://www.trobar.org/troubadours/

Troubadour Melodies Database. Katie Chapman did this work for her dissertation, and figured, why not share? It’s still in beta, so the look changes, and it can be scary if you aren’t a musicologist.

https://www.troubadourmelodies.org/

Trobaretz, the website of Courtney Wells, who has done a lot of your work for you in finding links to manuscripts so you don’t get lost at BNF or fall down too many rabbit holes.

https://trobaretz.wordpress.com/

The University of Cork has a collection of medieval Irish works in original and translation, called CELT: the Corpus of Electronic Texts. If you’re writing anything modeled on an Irish example, you have to know about this site:

https://www.ucc.ie/celt/

The University of Michigan’s “Corpus of Middle English Prose and Verse” features un-edited versions of Malory’s Le Morte d’Arthur, Piers Plowman, Chaucer, and other gems.

https://www.hti.umich.edu/c/cme/

The University of Toronto has a number of useful things from its library webbed. Among other treasures is the original 1609 printing of Shakespeare’s sonnets.

https://www.library.utoronto.ca/utel/ret/shakespeare/1609.html

The University of Victoria Shakespeare online.

https://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/index.html

The Traditional Ballad Index, hosted at Fresno State University.

https://www.csufresno.edu/folklore/BalladIndexTOC.html

You can find more of my articles on bardic and other arts at the Raven Boy Music website. https://www.ravenboymusic.com/articles/

Appendix 1: Adelaide’s Harangue on Copyright Violation

Understand this: YOU NEED NOT SELL COPIES FOR MONEY to be in copyright violation. Putting your lyrics up on a web page or printing lyrics constitutes both publication and copyright infringement. On my CD “Up the Great North Road” I covered the Stan Rogers song “Lies” and I have the lyrics available in the liner notes. Below the song it says, copyright Fogarty’s Cove Music, all rights reserved, used by permission. This means I have talked to Stan’s widow on the phone, discussed the project, and received her okay TO PRINT THE LYRICS. Printing goes beyond even performance rights; publication rights are governed by a whole different set of laws. The phrase “used by permission” indicates that a deal was made up front transferring the rights to publish for some consideration (which may be no more than good karma or “goodwill”) and demonstrates the copyright holder’s due diligence in defending their property. If copyright holders let you (and every other guy who does not seem to be profiting by it) get by with printing the lyrics, they may lose the right to sue the first guy who prints them for a profit. If you don’t go after everybody who didn’t ask “please”, you can lose your song.

When performing a copyrighted piece: again, you need not make money to be in violation. Any commercial enterprise going on at the site which can broadly be construed to benefit from your music means that royalty fees are due. This includes the site rental and any merchanting going on. When events were in church social halls and public parks, and no one sold anything, we were safe; those days are long gone, at least for large (kingdom-level) events. This law is why restaurants playing music must pay royalties. Their BUSINESS is food, but they are enhancing the dining experience by playing music and therefore they are gaining a benefit and they PAY. This is actually the site’s responsibility, so you, the singer, needn’t worry, unless you think it’s a problem if the site gets sued and they never let the SCA use it again. And who will know? Ah, little children, the boogie man has nothing on the spies of the American Society of Composers, Artists, and Producers, better known as ASCAP, and their cronies. Their job is to visit schools, camps, churches, dance schools, record stores, restaurants, and other places of business, commerce and congregation, and discover if 1) copyrighted music is being played and 2) said establishment has paid for the privilege. These days, they spend a lot of time trolling YouTube.

Would you take a knee cop off an armorer’s table without paying for it? The guy who buys it isn’t making money with it, but he is gaining a benefit, so he pays. Why is it so hard to accept that need when dealing with creative output? You as a filk writer are gaining a benefit every time someone applauds and fêtes you for your masterpiece, when much of the credit is due someone else. If you are filking a folk or “small-time” performer, they may give you permission; most don’t have any illusions that they’ll get rich off royalties. If the song is in the Sony catalog, good luck to you.

Copyright is the one area where I promise you, IT IS BETTER TO ASK PERMISSION FIRST than to apologize later. Most artists DO understand about non-profit-making musicians, goodwill, and potential generated interest in their product, but they CANNOT let infringement slide without endangering their livelihood.